Here what’s in store for you this week:

- Our reporters are facing a fresh spate of harassment and bullying after publishing a new batch of testimonies about extrajudicial executions in the southern Russian region of Chechnya;

- Pandemic-linked inflation arrives in Russia, damaging the lives of average Russians — but yielding huge profits for the state-linked oligarchy;

- We report on a suicide epidemic ravaging indigenous people in Siberia;

- Plus, this week we bring you a dispatch from Russia-controlled Abkhazia, which became a cryptofarming paradise — before mass closures.

Want to get the full story? Click the links below for full-length articles in Russian.

Growing Fallout from Our Chechnya Investigation

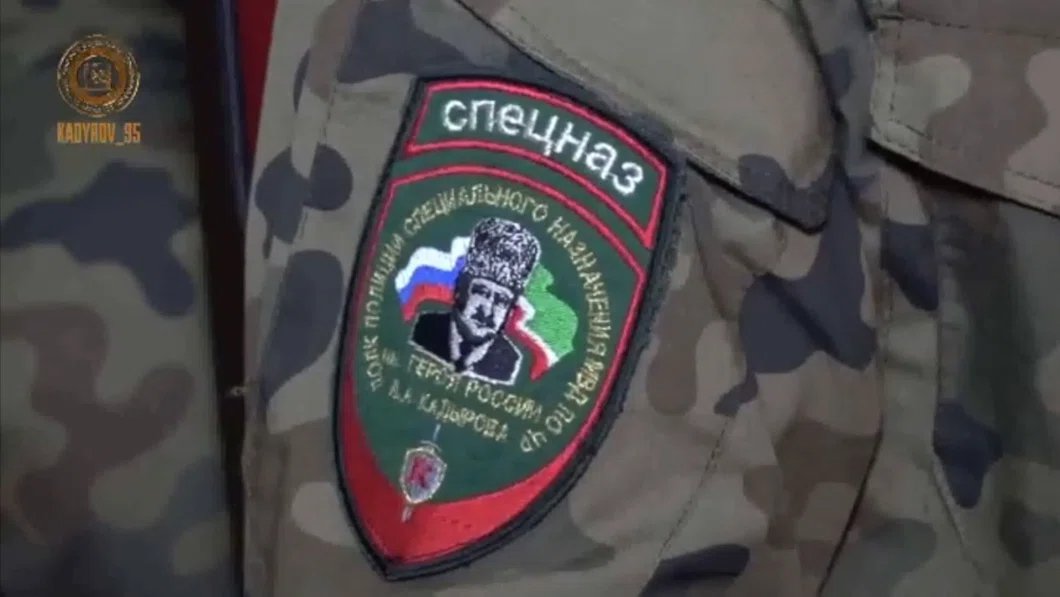

Last month we published a series of investigative pieces shedding more light on extrajudicial killings in Southern Russia, including the so-called 'gay pogroms.' Our award-winning reporter Elena Milashina has been collecting and fact-checking evidence confirming that Chechen authorities kidnapped at least 109 people over the space of several years. Many were executed. Milashina also secured testimony from one executioner who was directly involved. Publishing this new evidence unleashed a mass campaign of harassment and bullying by the officials targeting our newsroom.

'THINLY VEILED DEATH THREATS.' Our reporters have faced a fresh spate of all-too-frequent attacks and harassment since the publishing the revelations. Chechen authorities described our investigative work as "insulting and libelous." They even staged a public rally demanding the closure of our newsroom. Our Moscow office also suffered a suspected chemical attack last month. Numerous foreign diplomats, international media watchdogs, Human Rights Watch, and Amnesty International have all called on Russian authorities to prevent threats against Novaya Gazeta, with Amnesty International launching a petition to ensure the safety of Milashina.

FULL ENGLISH TRANSLATION OF INTERVIEW WITH CHECHEN WHISTLEBLOWER. Following the attacks and increased international attention to our investigation (especially, after our TikToks about it went viral), we decided to publish the new Chechnya exposé in full English here. In it, Milashina speaks to Suleyman Gezmakhmayev, a former Chechen sergeant. His testimony details numerous extrajudicial killings of prisoners in Chechnya that happened in early 2017. This is the first-ever public whistleblower account of the events.

'ALL DETAINEES WERE FIRST TORTURED WITH ELECTRICITY. ' In his testimony, Gezmakhmayev details the pervasive culture of violence during his years of serving in the Chechen security forces. However, the mass murder campaign underway in 2017 was especially brutal. Back then, Gezmakhmayev and others in the same unit were responsible for detaining and guarding some 56 prisoners in the unit's basement gym in Chechnya's Shali district. 'In every room of the basement, they installed a hook at the ceiling to hang detainees upside-down and dip them into a barrel of water until they started convulsing,' Gezmakhmayev remembers.

GEZMAKHMAYEV ALSO DESCRIBES THE CIRCUMSTANCES OF 13 DIFFERENT EXECUTIONS HE AND HIS COLLEAGUES WITNESSED. Most of these were Kadyrov critics or just random folks caught in the terror's net. Some of the detainees were kidnapped in the infamous 2017 'gay pogroms.'

"They tell you that you must go and torture somebody. They watch to see if you're holding his head underwater if you're torturing him with electricity properly. If you don't follow their instructions, they will either do away with you or, in the best-case scenario, will invent something to accuse you of. For example, collaborating with militants," Gezmakhmayev recollects in the interview.

EXECUTIONS WERE HAPPENING IN LOCAL MILITARY BARRACKS. Specifically, Gezmakhmayev recollects a group of 13 detainees killed there. 'They were kneeling along the walls in the same room with their hands cuffed behind their backs. Some of them begged for their lives, saying they were innocent. Security officials were mocking and insulting them,' Gezmakhmayev says. The next time he checked on the room, two detainees were dead, and their bodies 'were stacked one on top of the other.' Gezmakhmayev left his shift. The following day his colleague, Suleyman Saraliyev, shared his witness account of how the remaining detainees were slaughtered. According to him, two were shot and the rest strangled with a sports rope from the gym upstairs. Saraliyev claimed he was forced to participate in the executions. Later, choked by guilt, Saraliyev became obsessed with sharing his account with someone else. Gezmakhmayev suggested he runs for his life. Saraliyev was murdered in unclear circumstances right after that after his boss publicly claimed he was gay.

RUSSIAN POLITICAL REFUGEES FACE BUREAUCRATIC HELL IN THE EU. Gezmakhmayev fled Russia and claimed political asylum in Germany. But as is the case with so many other Chechen refugees, his application was denied — on a mere technicality. We helped Gezmakhmayev and his family to secure refugee status in another EU country. Still, it took two years of fighting the European migration system.

"The asylum seeker shall be granted asylum by the authorities of the country through which he arrives in the territory of the European Union. Hundreds of Chechens are being denied asylum in Europe today," Milashina explains. "Such a depersonalized approach does not account for the specifics and criticality of the reasons forcing people to escape from Chechnya and Russia."

BACKSTORY. Chechnya's autocratic ruler Ramzan Kadyrov operates under Putin's direct patronage and has essentially been given free rein over the oil-rich province. Region's massive corruption fuels monstrous income inequality and the worst human rights violations in Russia. Moreover, those who escape the region and seek asylum abroad are increasingly under threat. The Chechen authorities are known for ordering assassinations in Europe and using Interpol arrest warrants to go after dissidents around the world. Disappearances are common in Chechnya, where suspected dissidents, sexual minorities, and even members of the political elite who have fallen out of favor have been illegally detained, tortured, and executed. Many of our journalists were attacked in connection with the Chechnya coverage, and some got murdered, including Anna Politkovskaya. Kadyrov had previously made explicit threats against our investigative journalist Elena Milashina and us, following the publication of her expose on the region's repressive COVID-19 lockdown measures.

Read Gezmakhmayev’s full account and Milashina’s report here.

Indigenous Population Halves in Northern Siberia

This week our special correspondents Elena Kostyuchenko and Yuri Kozyrev published a big multimedia dispatch about the unreported suicide epidemic ravaging indigenous nations in Siberia. They visited the Uralic Nganasan community in Siberia's northern reaches, which is disappearing at a shocking rate. Just three decades ago, there were some 1,300 left. Now, there are only 700. Their report highlights rising tensions between the Kremlin and indigenous communities suffering the consequences of aggressive industrial development in Russian natural reserves.

NOMADIC CULTURE, FORCED TO SETTLE. The Nganasan are the descendants of semi-nomadic reindeer hunters, with ancient roots and a shamanistic spiritual culture. Colonized by Moscow in the 17th century, they were later forced to "settle" under the Soviets in the 1930s as nomadic "civilizations" were considered fundamentally incompatible with the government-sanctioned lifestyles. The Soviet enforcement of Russian literacy made the local language almost extinct. Similar to colonization practices of indigenous communities in other parts of the world, the Kremlin would take away local kids from their parents and send them to study in boarding schools.

"There, speaking Nganasan was forbidden, and teachers punished them for every Nganasan word they used — beaten with canes, kicked out of the class," Kostyuchenko and Kozyrev cite local linguist Valentin Gusev.

SUICIDE EPIDEMIC FULED BY ECONOMIC RUIN. Kostyuchenko and Kozyrev visited a Nganasan settlement of Ust-Avam in the Krasnoyarsk Krai, where there are more suicides than natural deaths. "Six people die here every year. One of these deaths is the result of natural causes. Two or three freeze or die drunk. And two or three kill themselves," write Kostyuchenko and Kozyrev. Devastating effects of global warming, human-made environmental degradation, and severe poverty fuel depression here. Out of 359 residents, just 54 have jobs.

"People crack, young people in general break down. The suicide rate is higher among young people. There is no work, nothing. Here you need to pay for lighting, and need to work for food. There is no food, no work, no money," a young resident tells us. Her sister also committed suicide, leaving behind an 11-year old son.

Поддержите

нашу работу!

Нажимая кнопку «Стать соучастником»,

я принимаю условия и подтверждаю свое гражданство РФ

Если у вас есть вопросы, пишите [email protected] или звоните:

+7 (929) 612-03-68

DESTRUCTION OF LOCAL FOOD SUPPLY. The catastrophic impact of climate change in the Russian Arctic limits the Nganasan's fishing opportunities — their primary food source. The government keeps restricting their hunting, too. This is a widespread source of tension between the Kremlin and indigenous communities elsewhere across Russia. With a de facto ban on hunting, the Nganasans stopped following the routes of wild herds, which weakened the entire population and led to reindeer husbandry's disappearance. Local lakes dry up, and reindeer herds thin out.

AGGRESSIVE RUSSIAN ARCTIC DEVELOPMENT EXACERBATES CRISIS. Our reporting on the Nganasan nation takes root in last year's coverage of the Norilsk Nickel spill, the largest human-made fuel spill in Arctic history. Back then, the Russian government colluded with the country's largest nickel producer to whitewash the disaster. The spill affected the environment that provided the Nganasan with basic food supplies. "They catch fish; they hunt deer. But there are no fish this year. And the deer left for other lands three years ago," write Kostyuchenko and Kozyrev. Last year, northern indigenous tribes signed an open letter to US business magnate Elon Musk and Tesla asking him not to purchase any nickel, copper, and other materials from Nornickel in the wake of the disaster.

BACKSTORY. The Russian government keeps expanding the industrial harvesting of natural resources deep into previously-protected nature reserves. All of this development takes place to the detriment of local indigenous communities, which have long had a contentious relationship with the Russian state. For centuries, Moscow has been erasing indigenous culture and denied these populations their rights. There has also been a recent spike in tensions between federal authorities and indigenous communities. Some of these nations mobilize against an over-centralized state, government-backed environmental assaults on their sacred lands, and claim back their autonomy. In Kalmykia, for example, the majority-Buddhist region protested against a Kremlin-appointed Mayor. In Buryatia, locals rallied against a rigged election for weeks. In a case that sent waves across Russia, a Sámi activist sued the government for extortion last year.

Read a special Novaya Gazeta report on the life of the Nganasans, the disappearing people of Taimyr, here.

Abkhazia’s Abandoned ‘Cryptoparadise’

Kremlin's support for separatist statelets in the Russian near-abroad fuels bizarre economic bubbles, as well as geopolitical issues. This week we examine the cryptocurrency mining craze in Abkhazia, a Russia-controlled breakaway region of Georgia. Fueled by Russian investments, farming cryptocurrencies placed a terrible strain on the regional electricity grid. They caused significant power outages — prompting a further ban. Our special correspondent Irina Tumakova conducted in-depth interviews across the region to assess the real-world impact.

BOOM AND BUST. Since 2016 Abkhazia has been one of the world's largest 'grey' hotspots for cryptofarming. Even local farmers and the elderly are very familiar with the term. Local officials estimate that hundreds of new cryptofarms have been established here. "Of those who do this, only about 10 percent are real professionals," one 'farmer' called "Sergey" told Tumakova (he requested that he be referred to by a pseudonym). "Some of us don't even know how to read, let alone understand the principle of blockchain," another local told Tumakova. Last year local officials abandoned futile attempts to fight it and legalized the activity. But the effort to rein in cryptofarming was a failure. The newly fueled boom caused severe rolling blackouts. It forced the statelet to import the electricity for the first time. Authorities shut the mill down once again.

CHEAP ENERGY PRICES FUELED CRYPTOCURRENCY BOOM. The region of around 250,000 people pays a tenth of the price for its energy compared to neighboring Georgia. Everyone spotted the window of opportunity at all levels. "Abkhazia may become the first country in the world to issue a national cryptocurrency," Minister for Economy Adgur Ardzinba suggested as early as 2018. After people hedged their bets on crypto, Abkhazia saw a surge in energy consumption. The new, welcoming attitudes towards mining crypto, combined with poor regulation, resulted in an unsustainable surge that benefited locals in the know but created a massive inconvenience for others, including the rolling blackouts.

"In the winter, when there was no other income — and especially during the pandemic, when the borders were tightly shut, it helped our family stay afloat," said the local cryptofarmer, "Sergey."

CRYPTOFARMING WAS INITIALLY BANNED HERE IN 2018 BUT WAS LEGALIZED AGAIN LATE 2020. 'Miners' quickly moved in, many of whom were Russians. "The lion's share of major mining farms that were established in Abkhazia before the ban were purchased with Russian money," Kirill Bazilevskiy, an Abkhaz business expert and creator of 'Abkhaz Projects' told our correspondent.

BLACKOUT. Authorities imposed a second ban after the energy crisis started to rear its head. In November, Abkhaz energy company Chernomorenergo instituted a rolling blackout. It started determining the excessively consuming areas — and sending police to shut down cryptomining operations. Officials reimposed the ban. Now all those who invested in the 'cryptoparadise,' and its required devices, locations, and workforce don't know where to turn, leaving a trail of unused tech equipment in their wake.

CRYPTOFARMS IN ABANDONED SANATORIUMS. The ban means that police have been raiding former cryptofarms in abandoned factories, former Soviet sanatoriums, or dilapidated residential buildings. Abkhazia has no shortage of abandoned buildings. Flour mills, candy and tea factories, as well as the old Soviet sanatoriums that once granted the region the moniker "Soviet Cote d'Azur" are crumbling into the landscape. This is a long legacy of both the Soviet collapse and the Russia-Georgia war in 2008. At the beginning of March, over the space of just a week, police discovered some 230 farms. After the mining ban, some former cryptominers were at a loss about what to do. "I paid money to a guard so that he would supervise my farm," said one. "When mining was banned, he started asking me to take everything out. He feared it would be his demise."

'CREEPING ANNEXATION' LOOMING BEHIND ENERGY CRISIS. The Kremlin has been recently pushing for greater 'integration' between the region and Russia. Abkhazia is already military and financially controlled by Moscow, after all. Russia recently pressured local authorities to sign agreements' harmonizing' various aspects of legislation along with the Russian law. Part of this 'integration' push is a consolidation of the now-troubled Abkhaz power grid. After talking to local political elites, Tumakova says that the annexation looming on the horizon seems to scare many Abkhazians. "We love Russia," Eshsou Kakalia, a former deputy prosecutor general of Abkhazia and now one of the leaders of the opposition movement Aidgylara, told Novaya Gazeta. "But we do not want to join Russia. It is not for this that we have been at war with the Georgians for independence for so many years, then to join Russia".

"We are following what is happening in Crimea after it got annexed by Russia," a former senior Abkhaz official told us. "If Russians start buying land from us, soon we will not be able to approach any beaches whatsoever."

BACKSTORY: Russia spends billions on geopolitical gambits every year. According to Russian authorities themselves, over $100 billion went to discounts and hidden subsidies for Ukraine’s pro-Russian governments and politicians before the 2014 pro-democracy revolution. After the latter, spending in Ukraine only increased — every year the Kremlin financially supports Russia-backed separatists in eastern Ukraine. Combined with Russia’s concurrent financing of disputed statelets such as Abkhazia and South Ossetia in Georgia and Transnistria in Moldova, we estimate that Russia spent around $32 billion on these places over the past five years alone.

Novaya Gazeta’s special correspondent Irina Tumakova, took a trip to the derelict Black Sea territory on the Russian-Georgian border. Read her investigation here in full and an abridged version in English, written by our Georgian partner, Jam News.

Other Top-Stories Russia Has Been Reading

- COVID-INFLATION: HOUSEHOLDS SUFFER, STATE-LINKED OLIGARCHS PROFIT. Pandemic-linked inflation has arrived in Russia, further damaging the lives of average Russians who have been suffering from pandemic-induced economic hardship and stagnating incomes. The annual inflation rate as of March stands at around 7.7%. Food price spikes have hit especially hard since 40% of incomes of Russians goes to buying groceries. Yet, our economics columnist Dmitry Prokofiev points out to super-profits Russian retail chains make out of it. The Kremlin’s policy of limiting foreign imports over the years made sure that the average Russian is left with little to no choice than buying overpriced and often low-quality foods made by oligarch conglomerates. Lower demands for foreign imports also mean that foreign exchange earnings remain in the hands of the few — not the many. The Kremlin-designed system guarantees that “even the most insignificant boss in a remote municipality finds a mechanism by which he can turn your money into his own,” Prokofiev explains.

Поддержите

нашу работу!

Нажимая кнопку «Стать соучастником»,

я принимаю условия и подтверждаю свое гражданство РФ

Если у вас есть вопросы, пишите [email protected] или звоните:

+7 (929) 612-03-68