1.

Our first day in Norilsk, the rain smelled like chemicals. Criminal proceedings had just been initiated against Mayor Rinat Akhmetchin for criminal negligence “demonstrated by a failure to fulfill his duties during an Emergency Situation.” The Emergency Situation: 21,000 tons of diesel fuel spilling and seeping into the Daldykan and Ambarnaya Rivers, caused by a ruptured fuel storage tank at Norilsk’s Heat and Power Plant № 3 (HPP-3). Yury Kozyrev, the photographer, and I froze in front of the city administration building for a few hours then headed to Kayerkan, a neighborhood far on the outskirts. Local scientist Zoya Anatoliyevna Yanchenko, the director of the agricultural and ecological research institute Arktika, had asked to meet us in a park. It was 9 PM, raining. The park was an empty lot with a plastic sign reading “I Love Kayerkan.” We met in a semi-enclosed gazebo. I knew what Zoya Anatoliyevna had already told other journalists: the fish in the rivers around Norilsk had strange mutations on their reproductive systems. I needed to talk to her about what had happened before and after the spill.

Zoya Anatoliyevna was beautiful, wearing a mask over her made-up face, a light pink scarf over her coat. It was cold. Shivering, we began our conversation.

Zoya Anatoliyevna told us her institute was entirely independent of Nornickel.

Then three policemen appeared.

“Good evening, ladies and gentleman!”

They asked for our documents.

“Oh, Moscow.”

They asked us about our assignment.

“Follow us, please. You are required to self-quarantine.”

Fresh COVID test results didn’t help.

I told them we were in the middle of an interview and they could wait for us to finish.

Fine.

They surrounded the gazebo.

Zoya Anatoliyevna changed her tone.

The fish really do have strange mutations, there are articles about it, but she couldn’t really speak to that, not being an ichthyologist. She couldn’t advise us about who else we could talk to. “These people – they’re not from here.”

She said, “I think everything will turn out alright in the end. The company will provide funding… As scientists, we are ready to help everyone, arrange everything. The most important thing is not to stir anything up.”

“We’ll definitely work it all out!”

She repeated this several times.

They held us in custody for four hours. The chief policeman kept saying, “If I had known you were journalists, I would have never approached you. “

“What a dumb coincidence,” Yury said.

And that’s what we really thought.

2.

What is Norilsk? It is almost the northernmost city in Russia. The only way to get there is by airplane, there are no roads, the only railroad goes to the neighboring town of Dudinka.

It is a border zone – when you arrive you have to fill out a form like you’re entering foreign country. Actual foreigners are only allowed in with special permission from the FSB.

Precious ores lie under the tundra. Copper, nickel, cobalt, palladium, osmium, platinum, gold, silver, iridium, rhodium, and ruthenium are all extracted here along with commercial sulfur, metallic selenium and tellurium, and sulphuric acid. Nornickel produces 35% of the world’s palladium, 25% of the platinum, 20% of the nickel, 20% of the rhodium, and 10% of the cobalt. This is almost all of Russia’s nickel and cobalt and half of its copper.

Precious ores have always been here, while the municipality developed slowly – first with the GULAG, then the factory, and finally, the city itself.

The Complex was built by prisoners. So was the city. Construction on the Complex began in 1935. This is considered the date of Norilsk’s foundation, although the city didn’t start getting built until 1951.

The city is encircled by the Complex, they are fused together.

Pipelines, pipelines, villages – dead and those still living, shafts and mines and smoke, and the rare larch tree, like a ghost.

In the winter, it’s -45 °C, in summer, it wanders between 10 and 30 °C. Two months of night, three months of day. While we were there, the sun never set, it didn’t even touch the horizon. The light felt theatrical. At night, which was indistinguishable from day, people would walk their dogs, teens hung out on the playgrounds. Various smokes streaked across the sky.

One hundred and eighty thousand people live here, and a third of them work at the Complex. The rest either work in the Complex’s service sector or serving those who work at the Complex. For the past 20 years, every mayor of Norilsk, including the current one, Rinat Akhmetchin, cut his teeth here, starting out at Norinickel.

So when did the spill happen? May 29th. Word didn’t reach “the mainland” – Moscow and Russia – until two days later. “Good thing they found out about it at all,” Norilskers laugh.

A fuel storage tank burst at the very bottom. It was the largest one, № 5. The crack, two and a half meters long, is visible from behind the fence. The tanks – the one that burst and the ones next to it – are covered in rust from top to bottom. Nornickel blames the melting permafrost, claiming it “moved,” but the people of Norilsk know that HPP-3 and the Nadezhda Metallurgical Plant both stand on a cliff. Although the permafrost really is melting, which is also common knowledge.

There simply was no berm that might have contained the spill.

The stream of diesel poured into the Daldykan River, flowed into the Ambarnaya, and from there, into Lake Pyasino. The Pyasina River flows out of the lake and into the Kara Sea.

According to official statements from the Complex and the Russian Federal Service for Supervision of Natural Resources Usage, RosPrirodNadzor, the fuel never reached Pyasino, Nornickel stopped it. But the first containment booms – floating barriers enclosing the spill – were only installed 36 hours after the rupture. The rivers flow fast, and the lake is very close.

Officials claim that an offshore wind kept the diesel out of the lake. This wind blew for two days straight and held back 21,000 tons – 350 truckloads – of fuel as it surged down the river. They repeat this story over and over – so often, it even seems like they might believe it.

So far, four people have been arrested: the head of HPP-3, its chief engineer, his deputy, and Vyacheslav Starostin, the head of the boiler and turbine unit. The petition to overturn the arrest of Starostin, who had only been on the job since January 2020, has already gathered 66,000 signatures.

“This isn’t where we should be looking for who needs to be held responsible,” “the people are very afraid,” “anyone could have found themselves in his position.”

3.

Our second day in Norilsk. We headed to Dudinka, the port that the metals are shipped through back to the mainland, to meet with the leaders of local indigenous nations. There are five of them here: Nganasans, Dolgans, Nenets, Enets, and Evenks. They still consider Dudinka their capital.

We met with them at the Department of Education. They stepped out to smoke, and when they came back, they asked us, “Are you having problems with the police?”

At the door, someone called out our names.

A young policeman, clearly uncomfortable, demanded that we explain who we were and what we were doing here in Dudinka.

Two hours later, he called me.

“When are you planning to wrap things up? You really ought to hurry up and finish. I am clarifying this for you: I have been given notice that you are also required to self-quarantine. You must fulfill this requirement. So if you choose to continue without doing so, we will be forced to take certain measures. In order to prevent this, you must… I don’t want to give you a bad impression or get into any kind of disagreement, I am not trying to have a confrontation. I’m just asking you – please hurry up and finish your work here and go back to Norilsk.

Elena Gennadievna, please try to understand me and don’t think of this as some kind of threat or anything … I just wouldn’t want you to run into any trouble here in the Taymyr.”

4.

We’d call people, arrange to meet, and then, they’d disappear. It happened over and over. Phones rung, unanswered; doors closed. We reserved tickets for a helicopter ferry and a day before our flight, they called us to say that policemen were boarding the helicopter, something is happening, your tickets are cancelled. We made arrangements with a boat captain then FSB agents showed up to his boat and asked, “We’re looking for drug smugglers, are you by any chance transporting any civilians?” The same agents talked to the captain’s boss to make sure that he wouldn’t take us anyway and the boss threatened to break his contract with him if he did. The head of a private helicopter company told us that Nornickel had requested that he not to do any flyovers over the spill and without their business, there won’t be any business at all, you do understand.

No, we still didn’t.

“You’re getting stonewalled,” our Editor-in-Chief told us.

Local journalists – Norilsk has two newspapers, one owned by the Complex and the other, by the administration – also knew we were there. They remember and love Igor Domnikov, who ran Norilsk’s only independent newspaper, 69 Gradusov[69 Degrees] before coming to Novaya Gazeta[and subsequently being murdered in 2000 –Trans.].They told us to send their greetings, but refused to meet with us.

5.

Ruslan Abdullayev, lawyer and head of the Moi Dom [My House] Alliance, spoke carefully. But he was willing to speak. We met him in his office. Norilskers believe that it was his letter about the fuel spill that ended up on the President’s desk.

For a long time, he was alone on the battlefield. Abdullayev has been filing public grievances against the city and Nornickel and defending them in court for seven years. His reason is simple: I am a lawyer, he says, I want to bring Norilsk back to the right side of the law.

He believes in the power vertical and social control. “It was precisely the social power vertical that was created by the President that we latched onto at the right moment, which, more or less, despite all the difficulties and deprivations that come with it, ended up working to our advantage. You could say that this channel of social and civic connection was effective.”

He loves the city, but he couldn’t say why, “something about it gets to you.”

There are no members in his organization, but there is a skeleton crew – eight lawyers. Labor rights, corruption, ecology. “You wouldn’t believe how interconnected they are.” Up until last winter, the roads here were covered in granulated slag that the city administration would buy from Nornickel. After a years-long battle waged by Ruslan, the slag was finally acknowledged for what it actually was: dangerous industrial waste.

“Norilsk is like a sanctuary for corruption. The things that go on here – you won’t see anything as shrewd or intricate in any other region.

I’m telling you, they brazenly took their waste – which they’re supposed to salvage – and not only sold it off but got money out of the budget for it! I mean, damn! And there’s not a single oversight agency, no officials who could try and say ‘Oh, we didn’t know that was going on.’ They all knew. They essentially facilitated it.

So then what happened. I started getting texts like, ‘Be careful,’ ‘Don’t carry anything on you,’ that kind of thing, like someone was going to try to pin something on me. There were anonymous tips against me saying I was a terrorist, a Wahhabist, a gun runner…”

One of these anonymous tips got him and his wife arrested. “After that, I doubled down.”

Ruslan told us a story: In 2016, the wind tore the emergency roof off of building 33 on Talnakhskaya Street. The sheet of rusted metal killed a young woman.

“The investigative committee opened up a case, investigated for ten months, then closed it. They’d opened it on Article 109 – manslaughter due to carelessness on the part of an individual completing his job duties. They closed it due to the absence of a violation.

Right now, they’ve reopened it for the third time, this time, through [Alexander] Bastrykin [Head of The Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation – Trans.]. He took the it away from the Norilsk investigators and assigned it to new ones who ended up finding the man responsible, he was the head of the management company.

He confessed. It was all set, we were just waiting for the final decision. Then suddenly, he must have gotten an order from the higher-ups, and it became no, no, I’m not guilty, I won’t say anything. The investigators kept at it. Now they’ve called in the lead engineer, the next one in line. That’s their protocol, and that’s how they’re doing it with the spill. They study the documents and figure out the line of succession – whoever comes next takes the rap.”

Ruslan doesn’t have any pity for Starostin or anyone else who got arrested from HPP-3.

“No matter how you cut it, he was the one liable, it’s in his job description. It was his duty to let people know! I tell everyone, everywhere, I implore them – cover yourself, file reports, write, talk, do everything in your power instead of just sitting there saying nothing then suddenly being the fall guy. That’s what he’ll be if he doesn’t talk. And that is his choice. That’s what all this is leading to, unfortunately – the 51st Article [the right not to incriminate oneself –Trans.] and an attorney from Moscow. That’s it! Why doesn’t he testify?

If he’d shown up and said, yes, I started the job in January, I did this and that, I talked to my boss, filed complaints, I told them, I surveyed the territory and I saw that it wasn’t in compliance, I saw that there were these risks. I made the people in charge aware, took all the necessary measures. In other words, I was doing my job right and did my due diligence to prevent a disaster. There’d be no question! And yet he didn’t! Not only did he fail to do that, he’s also keeping it quiet. He’s basically aiding and abetting them. How exactly were you exercising your authority, how much control did you have over the hazardous industrial facility entrusted to you? I’m sorry but you can twiddle your thumbs all day long but still not allow something like this to happen!”

I remembered the original definition of corruption – decomposition, decay, rust.

Ruslan Abdullayev was the one that Vasiliy Ryabinin, deputy head of the Norilsk RosPrirodNadzor, came to when he decided to publish his video.

6.

Vasiliy Ryabinin looks at us and says, “I’m not talking to you.”

He’s fit, in a button-down shirt, sitting at a completely empty desk. It was his twentieth day on the job at RosPrirodNadzor. He’d already handed in his resignation, but they didn’t want to let him resign. A younger colleague peeked in, saw us, and left. The button-down shirts of the investigative committee circled below.

“Try to talk to the head of RosPrirodNadzor,” Vasiliy said with a smile at the corner of his mouth. “Like, arrange for an official interview.”

In the forty-minute video known around town as “the suicide,” Vasily Ryabinin talked about how he was doing an inspection of the Red Stream (the pipelines are constantly leaking and the most unusual seepages are given these kinds of nicknames) when he got word of the diesel spill. About how the he and the head of the Norilsk RosPrirodNadzor were prevented from entering the site by Complex security, who were accompanied by the police. How they then walked down to the Daldykan and saw the stream of diesel fuel gushing out “like a mountain river.” A couple of shots of the river of red pouring into the river of diesel conveying an “overwhelming sense of catastrophe.” How they then tried to take a roundabout way back to HPP-3 but a van of armed men followed them.

The following day, Nornickel security department associates met with Ryabinin to ask how he assessed the situation.

Then, the local RosPrirodNadzor leadership directed him to only do water tests near the booms. They started circulating the story that no fuel had gotten in the lake – there was that wind. Meanwhile, no one had taken water samples at the lake.

“I got a group of people from our department together and told them that I believed that all of this constituted gross criminal misconduct. And that I didn’t want to deal with it like this. So give me my assignment in written form. To which they replied, ‘You have been taken off this inspection.’ And told me to write out a memo about how I was dropping out and hand into the agency leadership. They said, ‘Just put what you’re dissatisfied with in writing.’ Like that. I said that I would definitely do that once they gave me the directive to put me back on the inspection.

Because the reality is that this isn’t merely white-collar crime, it’s a crime against my children.

It’s hard having kids around here. Mine cry all the time, they beg me, ‘Please, Papa, let us go play outside.’ But there’s gas out there and I can’t shake the feeling that this is on my shoulders, that it’s my job to take care of this.

Because right now, I happen to be working in the exact department that’s supposed to prevent this kind of thing. And that’s not happening. Yes, I probably shouldn’t have done all this at once, I should have acted gradually, over time, but the spill forced my hand. As you can see, I was forced to do what I did.”

We stepped out to smoke. He told us, “I’m going to quit and leave town. I’ve done my part, I fought for what I had to.” He said, “The most important thing is keeping my kids safe. They can play outside when there’s no gas in the air.”

The Deputy Head of the Yenisei Inter-Regional RosPrirodNadzor, Aleksander Aleksandrovich Ivanov told us, “I’d talk to you, but I’d lose my job. Now leave.”

7.

“The Lord probably knows how to help us people,” said Ramil Sadrlimanov. He’s a believer, Orthodox. His car is old and it’s filled with icons. He said that one time, his heart stopped, and he remembers that feeling. He said, I have a son and a daughter, I need to lead an honorable life. Ramil told us about how he was an election observer when Putin was voted in and that “everything after that got turned upside down.”

He has a business, a bath product store. His friend Igor hopes he goes out of business, “so you can hurry up and run for deputy,” but Ramil doesn’t want to go into politics. He has his Sony camera and his car. He, Igor Klyushin, Ruslan Abdullayev, and Andrei Vasiliev run the Norilchane [Norilskers] Facebook group. Right now, it has 7,000 members.

Igor Klyushin used to be the deputy editor-in-chief of the Complex’s internal newspaper, but he says he was wrong about things back then. What was he wrong about? He’d heralded the coming of Vladimir Potanin [Nornickel’s largest shareholder –Trans.], fought corrupt labor unions, and believed that Nornickel would “build Western-style capitalism.” He quit in 2006. He is proud to have gotten out with a golden parachute: he has an Israeli passport and can leave Norilsk at any time. But for some reason, he doesn’t. “It’s a non-stop apocalypse around here.”

Ramil hid his car by the side of the road and Igor and I headed to the Red Lake – the Nadezhda Plant’s oldest tailings storage facility. We walked for a long time along rusted pipelines. New lights shone over the pipes in the polar daylight. The ground all around us had been worked over – after the spill, before the visits from high-placed officials, they had got rid of all of the little red puddles, then went over everything with a bulldozer.

The road turned. This was where KrAZ trucks dumped diesel-soaked soil into the Red Lake.

Smoke seethed from the reeking earth. An excavator tossed heaps of dirt over the red banks of the lake. Instead of answering any questions, with a smile, the driver rapped on his Nornickel coverall.

The guys got word that the contaminated soil was being siloed in the abandoned hangar across from Ground Transport Lot#5. We were surrounded by abandoned buildings. Ramil took a panorama while Igor climbed inside.

Ramil can’t climb around anymore, not since he was followed and beaten by Cossacks two years ago. His back bothers him. But tomorrow, all of Norilsk will see his post.

They only got real internet here three years ago. Before that, it was just satellite that was so slow, you could barely read text. No YouTube, no social networking.

Nornickel did the internet, too. They started implementing a SAP operating system, they couldn’t survive without developing the local informational infrastructure. The cable was laid from Tyumen, they put down it through the Yenisei River. And laid a landmine under themselves.

The group started out investigating corruption among local authorities, who had a penchant for buying greeting cards and bouquets for 40,000 rubles a pop. “Parks” landscaped with Astroturf. Thirty-six hundred and fifty municipal apartments that were standing empty while people languished on waiting lists for them.

And then, they got to the Complex.

Under the group’s name there is a line that changes color. It’s part of “the people’s” air quality and sulfur emissions monitoring system.

“Green means it’s breathable. Orange means you can breathe it half of the time and not everywhere. Red means run for cover.”

The Norilskers group became a major source for information after the spill.

But membership in the group is public.

In addition to this group, there’s also an “underground” almost entirely comprised of former and current Nornickel employees. They call themselves “the underground” as a joke, but their security measures are nothing but. When we met them, we had to turn off our phones and be diverted into specific cars. Many of them have already been “taken note of.”

They showed me the threats that they’d gotten and wouldn’t let me quote them. The threats were all written in very similar language: good, literate Russian, peppered with philosophical musings.

I thought to myself that apparently, someone was getting paid to write these. One was especially memorable, claiming that, “There is no future. Those who worry about it are hypocrites. Think of the present. The present can change very fast, and suddenly, you can find yourself completely alone.”

I’m grateful to everyone who helped us even though I can’t name you. Thank you all.

8.

Gas from the Copper Plant covers the sky and I’m breathing it in.

It really is hard to describe. A flat sweet taste coats my throat and sticks deep inside me. I try coughing it out but it doesn’t help – the sulfur dioxide is already inside of my lungs.

It starts raining and I get pulled under an awning. When water makes contact with the gas it turns into a low-concentration of sulfurous acid.

The next time I breathe in the gas it’s early in the morning. The streets are full of people, little herds of kids stomping around. Everybody just coughs a little. A third of the town breathes this at work every day.

They say that it used to be worse. Back when the Nickel Plant was still operating on the other side of town from the Copper, no matter where the wind blew in from, the air downtown had gas in it. It’s been four years since the Nickel Plant was shut down. Nornickel tries to pass this off as ecological activism. Former workers explain that actually, it was because the roof and machines were falling apart and they didn’t want to pay to fix them.

In the summer, prevailing winds swirl in and people do their best to leave town or at least send their kids somewhere else.

Nornickel has promised to develop a “sulfur project” that produces sulfuric acid instead of waste. This would be the company’s costliest ecological intervention, with a 3.5 billion dollar price tag. They’ve been promising it for a long time now and keep putting it off. It’s currently slated for 2025. The foundation is already in place and until recently, there was a fence up around it. The fence has collapsed.

A white company car drives around town measuring air quality. They’ve been producing less waste since the spill. Even though this is most likely because of the influx of important visitors, Norilskers are grateful to the Complex.

9.

Minister of Natural Resources and Ecology Dmitry Kobylkin, RosPrirodNadzor head Svetlana Radionova, and Governor Alexander Uss arrived in Norilsk. They were taken to the site of the spill, a meeting with representatives from indigenous nations (there was a tough selection process), and finally, to the cleanup site. They were accompanied by “the right,” handpicked, group of journalists. We did not qualify for this delegation. Transportation was being provided by Nornickel and they didn’t let us on the bus.

We were, however, allowed to watch the first five minutes of their meeting with the municipal administration.

The meeting room was filled to the gills. People leaned on the walls, watched the meeting on screens. I recognized Zoya Anatoliyevna Yanchenko. Radionova fixed the pearl bracelet on her blue glove. The Minister spoke:

“Our chief objective here is taking exhaustive measures to protect the wealth of natural resources and biodiversity… We have seen many attempts to weaken the legislation that protects our natural resources. Russian Federation President Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin has passed down an exhaustive directive about this. Today, we cannot say how much time will be required in order to restore these disrupted ecosystems. I don’t think it will be just a year. But from what we have seen, we would like to commend the highly professional work of the Ministry of Emergency Situations and their amazing efforts to localize and organize the future of the cleanup of this disaster…”

Nornickel representatives declared that they’d already cleaned up 90% of the spilled fuel.

10.

A Nadezhda worker:

“It doesn’t really matter where you work around here. Norilsk is the kind of place where no matter where you go, it’s a total nightmare. It’s truly a state within a state. In some regions, a salary of, say 35 to 40,000 rubles cash might be enough, but here in Norilsk, with our prices, you’ll pay 12,000 a month just for utilities in a two-room apartment. A salary of 100,000 rubles doesn’t go far, even though that’s how much a smelter makes. Not everyone at the Complex even gets that much. Especially considering the fact that the price of that 100,000 is, putting it lightly, your health.

The rates don’t correspond with the market throughout the rest of Russia. If we had the same rates they have on the mainland, in other regions, our salaries would be many times higher. I mean many times. Those same smelters would be getting around 200,000, and shaft workers, too. But nobody here makes that kind of money.

The inspectors all have ties to the Complex. What kind? The most basic kind. There’s one who taught at the corporate university, and that’s a branch of the Complex, too, it’s where all the workers get trained. The oversight agencies – all of them are connected like that. Former plant safety tech inspectors get jobs at the [Federal Service for Ecological, Technological, and Nuclear Supervision] RosTechNadzor. Or RosTechNadzor people come work at the Complex.

I don’t think anyone will manage to change much of anything around here. But sometimes, independent agencies do show up. They write up reports that no one ever sees.

The workplaces… There are standards for going over the permitted levels of particle concentrations. Rules about noise, gas, vibrations. All of those exist, all those standards are established. But when they do inspections of, say, the dust, they do them when a department isn’t actually operating! They come, naturally, during the morning shifts. Everyone knows when they’re coming and that’s when they schedule maintenance work. So what exactly gets inspected? Clean air? And I’ve never seen a single monitoring test on vibrations. With that, it’s like everything’s more or less fine, but then people get out of work and their backs really hurt. Like if your job is just to sit there and oversee whatever processes, because of the vibrations, at the end of the day, you’ll get up and it’s like you can feel every vertebra in your spine. And if anyone tries bringing it up, their complaints don’t go any further than their department or at most, the Complex. Word rarely gets out.

They don’t allow any photos or videos, and if you get caught, you’ll be fired. Even for regular pictures, like taking a group photo at work, there’ll be consequences. Including losing your bonus – that’s totally normal. There were cases where the guys took photos together and posted them on their social media, their personal pages. You couldn’t see any kind of problems, they were just pictures of them at work. All of them lost their bonuses.

How much of your income is your bonus? Minimum, 30%, and it goes up to 50%.

A lot of the workers are in debt to the company. They take out mortgages, credits. It’s Complex-sponsored soft slavery. They pass it off as social projects, “My House,” “Moving Help.” But people end up signing papers and after that, they can’t say anything.

It’s never spelled out but everyone knows about it, everyone goes through it. All of those programs are approved by the supervisors. So like a person will apply to participate in some program, receive some kind of benefits or buy an apartment through it. They get your direct supervisor to sign off on it, and then that’s it, it goes all the way up the chain. So many signatures – everyone up to the head of the factory, everyone finds out that now this person’s enrolled in that program, they’re getting this or that. And then everyone – everyone – knows that they’re like a slave now. You think that guy would turn around and say, “I won’t work in a dangerous facility”? Two years ago, the roof caved in at Nadezhda. Do you think that that guy can turn around and refuse to go work there?

Building and facilities repairs at the Complex – that’s a whole separate story. Everything is falling apart. The tank that ruptured – it was a symbol of the Complex as a whole. That’s how everything is. Take the Norilsk Enrichment Plant – there’s a few areas there that are downright frightening. Like this elevator bay, it’s been in horrific condition for years. If you go up and you don’t take the elevator and take the stairs to the bay, there’s holes this big in the walls. And all of that sways in the wind. If you look at the the staff, you desperately need building and facilities engineers to go down there and fix it, but no one is willing to. Nobody wants the liability. Everything is in such terrible shape, if you take that job, that’s a one-way ticket. If a wall crumbles, it’s gonna be your fault. The roof caves in, that’s on your head. Because in order to fix things, you need to stop work. How are you going to get them to do that… How? How are we supposed to keep working?

Right now it’s all cranking along at full speed. This past year, 2019, it was pure profit. The entire Complex had insane numbers, Nadezhda produced more than it’s ever had in its entire history! They were doing a crazy number of experiments in smelting, they brought in all these different materials, shipped all this stuff in. Meanwhile, the machinery was just screeching and clanging along. Best case scenario, they’d come in and lubricate, weld something up real quick, and that would be that, back to work. What’s lubricating going to do when everything’s crumbling on the inside? Naturally, they try not to stop the ovens. Stopping the ovens is a big no-no because then you have to start them back up and that is a whole ordeal.

Imagine, you got this drum spinning right here in front of you and there’s molten metal just pouring out of every crack. Until there’s half-meter shell of hardened, spilled metal and the walls are crusted in it, people will try and get away with just sealing up cracks, putting patches on them.

I doubt that any of the smelters would be willing to talk to you. But you can ask them to show you their arms. They all have burns going all the way up to their elbows.

Because they get sprayed all the time. The felt, all of the personal safety equipment, it works, but when you’re holding a spur (a smelter’s tool – a hollow rod used to aerate molten metal during smelting — Е. К.) and the metal keeps spraying at you, what are you going to do, put your spur down? That’s dangerous! No. We get sprayed and we deal with it.

So many problems but no one says anything. There were people who tried to talk to some people who were further up. But they would just tell them that what they were describing couldn’t possibly be happening. It was impossible. We went through this training course at the corporate university and some higher-up from the Polar Division was lecturing us. People started asking him, what are you talking about, we were committing all of these violations on orders from our own supervisors literally yesterday.

“You can refuse!”

“Then we won’t get our bonus.”

“That’s impossible! You have it great over there! Everything’s wonderful! Your working conditions are perfect!”

If anything ever goes wrong, it’s your fault. There are various standards, something like dynamic risk assessment. You didn’t assess the risk correctly. That’s it, it’s your problem. You shouldn’t have done that.

There were completely absurd cases with that. Like five years ago, a man got out of his car around the Central Ground Transport Lot and was attacked by stray dogs. He walked out of his truck and got bitten. What could you blame him for? He got attacked by a pack of dogs. “He didn’t correctly assess the safety of stepping out of his vehicle.” They got him treatment then penalized him. Bullshit, right?

On paper, we do have a union. No one has ever heard from them. It’s an organization of Complex workers that’s affiliated with the Complex, but nobody knows who exactly these workers are. They don’t play any part in the life of the company at all. Then, when it’s time to have certain discussions with the management, collective bargaining, renewals, they come out of the woodwork and start doing things like putting together deals, we’ll give you more here and not there. In the end, our contracts get worse every time. The things that the workers care about are routinely ignored. Even simple things like transportation to and from work. You’d think that was a normal thing. How hard is it to take people to work? But no. It’s expensive. What for.

Ecology! You’ve seen the pipes, right? They don’t just stick out of the ground, you have feeder pipes leading to them. They’re vertical and then there are horizontal ones that take the gas itself out of the factories. Sulfur, all of those chemicals, they leave behind residue. I mean crusts. The pipes get clogged over time, they get covered in crusts. What do they get clogged up with? The same thing that gets in the air, sulfur dioxide. They need to be flushed. When sulfur dioxide mixes with water, you get sulfurous acid. The only way to clean them is by washing that out. And where does it go after that? Where does it run off to – do you think anyone oversees that? Nope. It’s only a stream of acid. This is a private enterprise. They pour it into the soil and then it’s gone… bye-bye. This is how things have been since ancient times.

Yes, I was born here. You don’t get much choice about where to work. There’s nepotism and really, it’s really bad, it’s actually one of our biggest problems,

at the Complex and with everything else that’s going on. Because a lot of the time, people get jobs that they’re simply not qualified for. They buy their diplomas then someone gives them a desk to sit at. The fact that they are responsible for other people’s lives doesn’t occur to them. They’re just working and doing their job. And then they go up the ladder. As a result, our leadership is completely unqualified. Just totally.

It gets ridiculous, people don’t understand the processes, they don’t know how the equipment works. And these are your direct supervisors! They don’t know what the machines are made out of. You know and they don’t. How does that work? People are trying to change that right now. They’re bringing specialists into leadership roles, which the local administration isn’t happy about. And everyone understands why: it gets in the way of the corruption, the kickbacks, all that. All of that happens. Kickbacks can go up to 50-60% of a contract. The people in charge of contracts know how it’s done… they can just refuse to sign off. They won’t close the contract and that’s it. You’ll do the job and they won’t pay you. They’ll find a way.

Not many people talk about the spill, they avoid bringing it up. Everyone knows that it’s just the tip of the iceberg. That tank kind of represents the entire Complex. Like, everything around here is that rusted and corroded. The spill – what are they gonna say, that it’s the plant’s fault?

Right now, they’re sending people out to clean up the spill. That’s messed up, too. At first, they were just having them clean up the trash around around the site because the big bosses were gonna arrive, better tidy up for them. There’s so much trash everywhere, you wouldn’t believe it. Now, they’ve finally started doing the reagents. They pour those reagents into the water in order to allegedly restore it. Everyone who could have been sent out there was sent out there to work on it. I mean, the people whose work can be put off, like the maintenance staff that’s still at the Complex. They’ve all been sent out there. And everyone knows that what they were doing for the first several days was just total nonsense. I mean, not total nonsense – picking up trash, cleaning up, that’s good, too, you do have to do that sometimes. But when you’re on top of a true ecological disaster and you’re just walking around picking up bottles, it’s… I don’t know.

And that didn’t even start on the 29th. It started like a day before Potanin was coming to town. Around the 3rd or 4th of June, they started cleaning up the grounds.

They aren’t scared of anyone else, but Potanin – you better clean up.

11.

“The people here are so trammeled that the only problem that they can see is the price of fish going up. What are you supposed to do with these people? Every nation deserves the government and conditions they live under.”

We met Vasiliy Ryabinin the day after our first failed attempt to interview him. With our phones off, almost at night. In the same apartment Vasiliy got for his family and began remodeling but is now selling.

The apartment is empty, the walls are covered in spackle. The windows look out on Lake Dolgoe under a lattice of rusty pipes, the HPP-1 cooling system, and the carcass of a demolished building. A ham radio hangs out the window, catching transmissions from hikers, hunters, and fishermen. The most distant signal it’s ever caught was 154 kilometers away. Vasiliy is a member of the local hiking society. He’s walked all over the Taymyr and paddled down all of its rivers, he knows exactly how fast they run.

He started working at RosPrirodNadzor on May 20th, as the deputy head. The Norilsk department itself is brand new, they had just opened it. Before that, Ryabinin didn’t work for six months. He went through a series of interviews, traveled to Krasnoyarsk for confirmation of his appointment. His first week on the job was spent getting his boss in Krasnoyarsk up to speed regarding the situation on the ground here in Norilsk and transporting computers. Then, they did their first inspection together, surveying the Red Stream, which runs by the Red Lake and into the Daldykan River.

The prosecutor they were doing the inspection with said, “You’re aiming too high, they won’t let you work like that.”

“I thought that if they were going to put pressure on me, I would leave after six months, at the end of my trial period. But that’s not how things worked out.”

He said, “My decision has cost my family around 400,000 rubles of my six-month salary – not enough to sell out your motherland.” He laughed.

One day later, he’d quit. They’d refused to fire him so Ryabinin was forced to remind them that he was on his trial period. He isn’t a lawyer, he is a chemist, but he has no trouble finding his way around complex paperwork, including legislation.

Ryabinin is a company man. His first job was at the Mining and Metallurgical Research Center (GMOITs), a scientific institute owned by Nornickel. Then, when the Complex didn’t need science anymore and the scientists were “optimized” away, he went over to RosTechNadzor and levied fines against Nornickel. He says that inspectors need time to grow into their duties, “It takes at least three years to learn how to do your job.” After that, he got hired at Nornickel’s security department. He said, “They wanted to get rid of me at RosTechNadzor, so I got rid of myself.” He said, “I was following the money.” Six years later, he was told that they no longer needed him at the security department, so he quit. Would he have quit if they hadn’t suggested he leave? It’s unclear.

He understands how the system works perfectly well and in that lies his great strength.

“Why am I quitting now? Because I’ve been relieved of all of my duties. [RosPrirodNadzor head Svetlana] Radionova said, thanks to you, I’m a YouTube celebrity. If you’re so smart, why don’t you think of something to do and do that? I told her, I want to do an inspection of the left bank of Lake Pyasino. She says, you’ll need a helicopter, we’ll get you one, go and take samples. I prepared in earnest, planned out the route, the sample capacity. Then they told me we don’t have a helicopter, take a mattress [a watercraft on an air cushion–E.K.], you said you’d be willing to go on foot, so go. They dropped me off there, I walked 10 kilometers through those swamps. A helicopter flew over me… The truthis that other people’s opinions hold a sway over you, even if you’re convinced of something. You start doubting yourself. I had to find that diesel, to prove it was there, at least for myself. It smelled like it, but a smell isn’t enough.

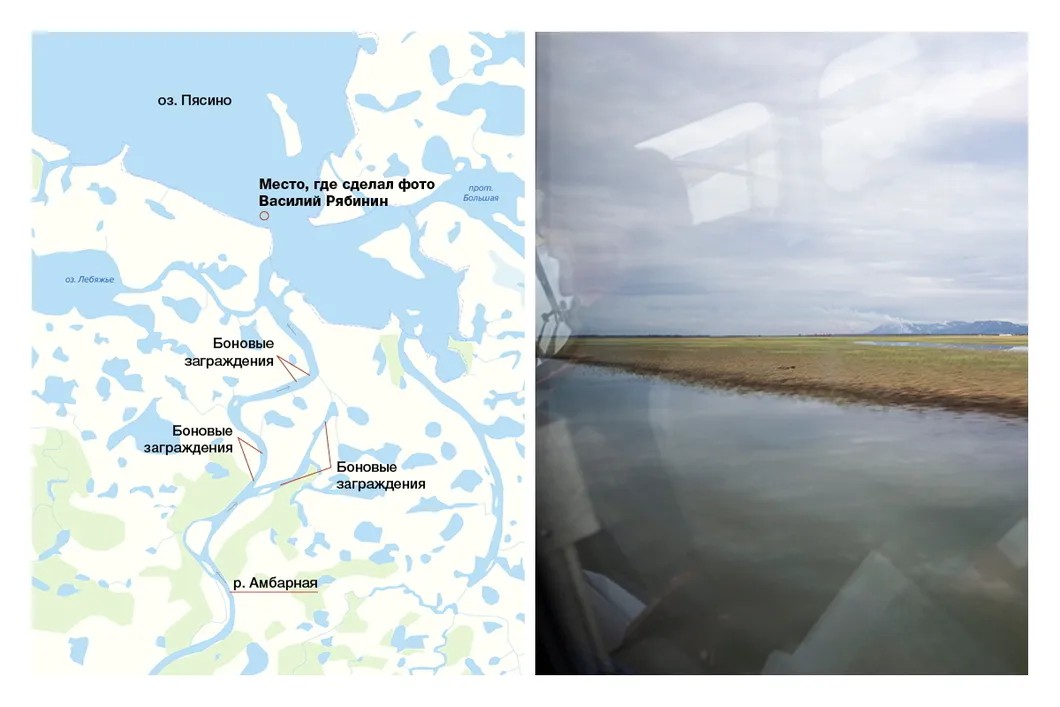

Then, when they were taking me back up the left branch of the river, I stuck my head out of the boat and I saw it. Now I’m sure I was right. I managed to get a few photos.

That’s Lake Pyasino in the one on the right, the left bank, with the tributary from the Ambarnaya River. Along the shoreline, you can see the residue from the stream of diesel fuel that flowed through it.

“On the left bank?”

“Yes. It’s covered in a ten centimeter-thick layer of diesel. That’s on the other side of the booms. If diesel passed through there, that means it’s long gone.”

Vasiliy referred to his new bible, Dr. Stanislav Aleksandrovich Patina’s Oil Spills and Their Effects on Marine Environments and Bioresources.He said that according to Patina, “It’s usually impossible to clean up more than 30% of a spill and, under the best possible conditions, no more than 70%. The wind needs to be at least ten times faster than the speed of the water in order to stop the flow of the spill.” He talked to Radionova every day. “She keeps trying to catch me doing something wrong. On the very next day, she had a whole dossier on me – what I’d inspected, when and how.”

Vasiliy also got a call from Minister Kobylkin, who told him he could call him if he ran into any problems.

After walking those 10 kilometers down the shore of the lake, Vasiliy had dialed the Minister’s number.

“What did he say?”

“Nothing. That’s when I said I was resigning. Let me leave in peace, don’t put any spokes in my wheels.”

“If I didn’t know about how fuel moves, I might also believe in the wind story. But there’s just no way! That wind could slow down the spill by 3-5% at most. That’s it! The direction of the diesel would be practically unchanged. It kept flowing down the current it’d caught. I wrote all this out with references. Radionova’s jaw dropped. You can argue with Ryabinin, but if Dr. Scholar wrote a book about it, what do you say to that?”

He said:

“I’ve worked at RosTechNadzor. I know the whole Complex, I’ve been all over it. Not a single one of their chief engineers has visited as many sites around here as I have. I can tell you where I haven’t been: I haven’t gone down the shaft at Skalistaya mine. I didn’t go underground at Komsomol, though I did visit the site. Everywhere else, I know like the back of my hand, I know all the issues there. I can tell you what’s going to blow up tomorrow and what’s going to collapse. Nadezhda. They don’t fix anything because they need to keep producing the metals. They’re trying to conserve resources. It wasn’t for nothing that in Soviet times, they had standards for maintenance. As soon as they started cutting corners, the deaths began, the injuries, constant liquid metal spills that they cover up.

It would be interesting to invite government sociologists here and use the Complex as case study of the entire Russian government system. Take Potanin as the President and go from there, what it’s like, how things work. There’s just so much effing corruption.

The people who run the Complex are just like the ones who run the government. They take good kickbacks despite already having huge salaries, for example, the head mechanic. They try to get away with things like, ‘This part isn’t completely worn out? Well, let’s not replace it then.’ That way they save two billion on maintenance and that’s another 400,000 in your pocket, give or take. There’s huge corruption within the company. It’s so destructive. Essentially, it’s a social issue created by capitalism.

Potanin is just as insulated from real information as the President. I worked in the security department. A letter from Norilsk could never reach the headquarters directly. No matter what you did. There were people who tried to take letters directly to Moscow, there’d be an outrage, how did that go over the heads of the Norilsk leadership and get out there? However, most often, the people who do things like that can’t actually articulate the problems well enough for them to get solved. If someone were to write to, say, Potanin, directly, saying that ‘It’s a complete mess over at DFEM,’ people would lose their jobs on the spot.”

“What’s DFEM?”

“The diesel fuel emergency management. Those barrels.”

“All sorts of people do the inspections, too. Really, all kinds. You couldn’t say that everyone coming from RosTechNadzor is taking bribes. Although of course I know people who do. They don’t really get anything good out of it. Because it’s the Complex. One wrong move and they’ve got you on the hook. If I hadn’t done anything, I’d be on the hook, too. We spilled so much diesel, it’s unbelievable – so where were you when that happened? It’s not like they don’t know the legal by-laws and ins and outs. They’ll say that if you don’t want to do it our way, some random guy will file a complaint and they’ll start checking out how well you’ve been doing all your inspections. You signed off on that, remember? They’ll run an audit and it will turn out that you weren’t fulfilling your duties after all.”

I asked him how he felt about the people who had been jailed. He said:

“I’ll tell you a story. Then maybe you can tell me how I’m supposed to feel. I oversaw gas at HPP-3. They have a gas distribution station. You have to open these flues there, little pipes with knobs on them, for venting excess gas into the atmosphere. The flues are supposed to point up toward the roof. I got there and there were no flues. I said, ‘What the hell, guys, what’s going on here? You’re going to have gas accumulate, a spark goes off, god forbid, and all of this will explode.’ I wrote out a directive. Then I came back to see whether they had complied. They’re like, ‘Yes, yes, of course, we did everything!’ This was the director of HPP-3, understand? Not just some gas service supervisor, but the director himself! He goes, ‘Let’s have some coffee. You can see everything out of the window of my office, we’ll take a look from up there.’ I tell him, ‘I don’t think so, pal, that’s not going to work on me.’ So we climb up in there. I look up from below – yep, there’s the flues… I climb the ladder up to the third story. The director is climbing behind me.

Then, something got into me and I decided to reach out and jerk on a flue. It came off in my hand! Understand? They had just stuck them into the snow! They’d soldered some legs onto them and stuck them straight in the snow! Can you imagine how I felt?

I wrote out the maximum fine, the highest possible amount for that violation. What am I supposed to feel about that guy now? I don’t know! Can you imagine what would have happened if I hadn’t checked? If I’d said, ok, let’s have some coffee? How are you supposed to trust these people? I’d be the one accused of negligence. You know, when there’s a gas explosion, it rips away all of your clothes and only your body flies up in the air. You end up a naked corpse on the ground.”

“Do you know why they put the booms out on the Ambarnaya? Because that’s the boundary of industrial zone. The fines for polluting industrial zones are practically nothing. That’s what they must have been thinking at first, ‘It spilled, so the hell with it. Look, we stopped it with our booms.’

Here’s my memorandum to Radionova on the monetary damages. I wrote a best practice where the damages are accounted for in a totally new way. There’s this method called resource equivalency. In order to restore the biodiversity of various natural resources, the damage to the marine environment is calculated based on the cost of restoration – i.e. the ecological services required at damaged area for whatever period of time. The calculations account for the loss of relatively basal conditions as well as the compensatory measures taken to reestablish them. In other words, in simple Russian…

What do we have right now? Potanin shows up and asks, ‘How much do you need? If you need 10 billion, I’ll give you 10 billion. You need fish – I’ll release some fish.’

But if we’re using resource equivalency, what we tell him is, ‘Sorry buddy, we don’t need your money or your fish. You need to come up with how to restore this ecosystem. You’ve screwed up everything from Pyasino to the Kara Sea. Now restore it. Or restore the biodiversity in the neighboring river.’ Then what is he going to do? He’s not going to waste his money on throwing his fish in there anymore. Because they’re going to die in that water! And therefore, no increase in biodiversity. No. First you need to stop dumping your waste and somehow clean it up or wait for it to get clean again. Then you can bring in your fish. And since all of that is on you, all of those labor costs, you’re not going to waste your resources on nothing. You wouldn’t plant trees if they were just going to die the following year because then you’d end up spending your money like that forever. That’s it!

And instead, we get ten billy from the lord’s purse, here you go, do what you want with it, I’ll just be over here polluting.

…Nobody cares what I wrote. But it should actually be the law. We need to reform our ecological legislation. We need to completely rethink the idea of responsibility.”

Vasiliy slapped his hand on the torn-up wall. He said, “I don’t know if I’m doing the right thing talking to you guys. You’re going to turn me into some kind of hero. I haven’t decided whether I want to be one. People are scared of heroes, no one around here needs them.”

12.

The Security Department, or SD, is a small special services division within Nornickel. It used to be called the Directorate on Economic Safety and Order and the old acronym, DEBiR, is what people still threaten each other with in Norilsk.

The department has 80 people. Most of them are former enforcers from the FSB or the police. Sometimes, there are interesting perversions. For instance, the Deputy Head of the local FSB Pushkinov’s wife used to work there, “and she’d always get very good bonuses.”

Although the security department is supposed to be concerned with the protection of facilities and prevention of theft, in reality, they do just about everything. There are a lot of different departments within the SD. For example, the department for “monitoring the situation” – it’s a factory town and nobody needs a revolution. The department of internal safety, hunting for bribe-takers and embezzlers. There’s a department for the safety of technological processes, monitoring production errors.

SD associates monitor social networks and forums, making sure that nobody posts photos from the facilities and punishing those who do.

There are also two mechanisms for external monitoring.

Friends from the FSB and Ministry of Internal Affairs (MIA) inspect mail and tap phones. The SD works closely with local law enforcement. They also join forces with them to provide security for visiting VIPs.

Of course, the SD also performs its stated duties. Say some drivers are pilfering diesel from the locomotives, pouring it into soda bottles and tossing them at the crossroads. The department will send out its agents to hide in the bushes in night-vision goggles.

But those are the unlucky few.

SD is part of Nornickel’s corporate security system. Two years ago, corporate security committee chairman Vladislav Gasumyanov, who’d come out of the FSB, was replaced by the harsher Sergei Barbashov, formerly of the MIA.

Armed men from this department were the ones who kicked inspector Ryabinin and his boss out of the spill site.

It is with the approval of this department that all water and soil quality tests are taken out of Norilsk. I was told this multiple times by multiple people – geologists, policemen, former SD associates. They explained the mechanism: you go to Ordzhonikidze 4A, where the department is headquartered, hand in your samples, get back a stamp on your documents and special seals on the bottles then, after that, the transport carrier police will approve the shipment.

There’s no way that really happens, I think to myself.

They tell me, “You still don’t understand where you are.”

13.

The city says: Foreign interests lie in the Arctic. Russia has already messed up so bad, they can’t wait to take advantage of that. Better not draw more attention to the spill.

The city says: Our wildlife sanctuaries are doing well thanks to Nornickel. Why would anyone want to bite the hand that feeds them?

The city says: Those who don’t make friends with the Nickels don’t make friends with common sense.

The city says: If there is no Complex, there is no us.

The city says: Why did you even come here?

14.

A cramped little apartment with homemade furniture. Vasiliy Ryabinin’s wife Irina is delicate, blue-eyed, wearing an orange shirt that says “Mama.” She picked up the walkie-talkie and said, in English, “Arseny, Vsevolod, come home now!” Two young boys, seven-year-old twins, ran in from the courtyard which is filled with pipes springing fountains of water. Two-year-old Adelaida was playing doggy and her Papa was scratching behind her ear.

“They’re still little, they don’t know anything. They think I’m a hockey coach.”

I asked Irina how she was dealing with everything and she said, “I’m fine. For better or worse. I vowed to support him.”

Vasiliy quit his job. They’re supposed mail back his employment record book. He ended up having worked for a month. In the morning, he had a fever, but he still asked, “So, are we going?”

We got to the railroad juncture by the Oktyabrsky mine and, climbing under the pipes (they’re everywhere), we trailed off into the bushes.

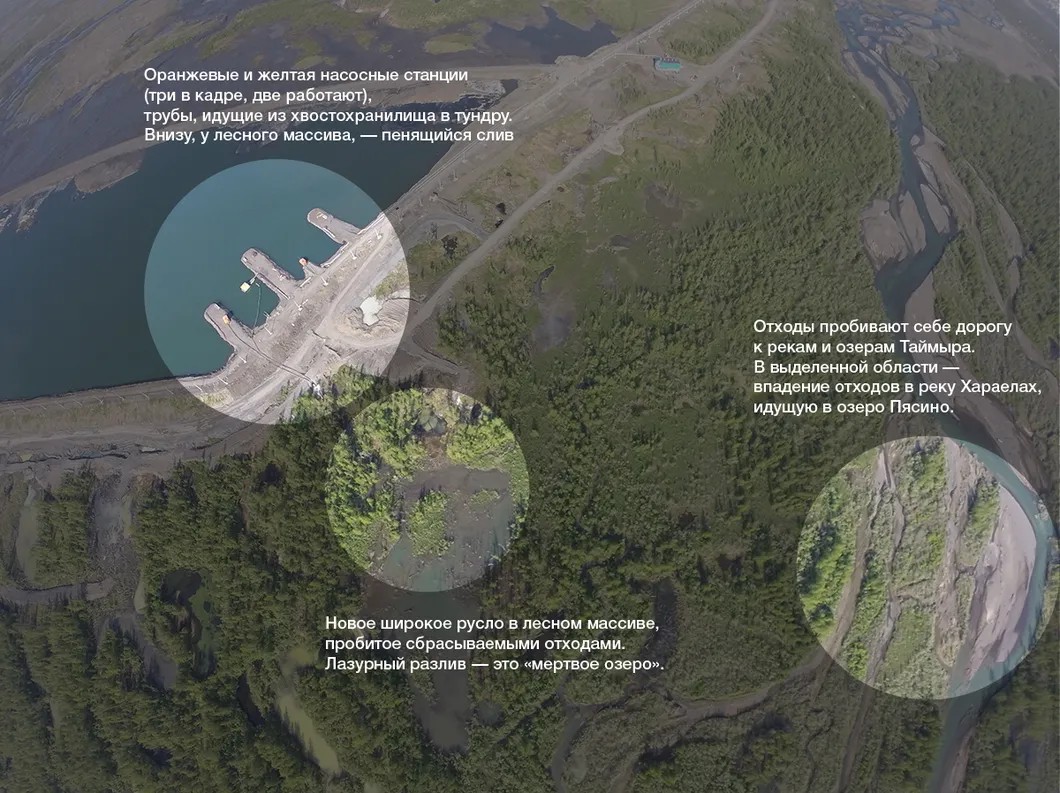

…A man stood on the roof of his car like a black signpost. He was looking in our direction, but he didn’t see us. He didn’t move. Next to him, a blue hut, the first security checkpoint. Behind him, the road that led to the tailings storage facility of the Talnakh Enrichment Factory, TEF. It’s a new tailings facility, it’s only been operating since 2017, but it’s already surrounded by lakes of every color, from azure to yellow. We’d seen them on Google Images. Vasiliy believed that liquid was seeping out of the tailings dam. Even though it’s new, it’s not hermetically sealed. We were trying to walk to those lakes.

The man on the roof of the car raised his hand with the binoculars.

We were expecting security, but not like this.

“This isn’t normal,” Vasiliy said.

We turned to penetrate deeper into the tundra. There were three of us. Me, Vasiliy, and his sister Maria -- Masha. She’d come from Achinsk to take the kids but she came with us because she didn’t want to leave her brother alone. She’s two years younger than him, her hair is in braids, she laughs easily. Vasiliy’s temperature was rising and she was making sure he didn’t forget to drink. We had 7.5 kilometers to go through the forest and tundra.

The Complex felt far away. A partridge flew out from under a larch and we saw its nest blanketed in colorful little feathers. A rabbit hopped over a pile of ore.

The tundra was carpeted in flowers. Very strange plants – flowers from the temperate zone, but with very short stems, and then completely unfamiliar ones. Long-tailed blossoms twisted from hairy green cords, blue forget-me-nots, menacing wild rosemary. Chartreuse polar poppies. The mosquitos swarmed around us, blocking out the light. We stomped up and down hillsides, bushwhacked through underbrush, jumped over streams. Masha landed and said, that’s how I’m teaching my kids to do grand-battements. She’s a fitness trainer, she teaches cheerleading and tells us about the tricks.

Vasiliy expertly ran over branches and stepped into thickets. “You’re lucky I’m sick. Otherwise, we’d be flying through here.”

We passed three more security checkpoints. Vasiliy’s mood deteriorated. “There didn’t used to be so many.” He pulled a gray cover over his orange backpack and quickly mumbled something into his walkie-talkie.

We advanced along the right bank of the Kharayelakh River.

At a certain point, we turned into the woods and walked along a strange, murky stream that poured out of a lake.

The lake was dead. Trees stuck out of it like oversized sticks – no branches, no bark. A strip of dead bushes along the shore and dead and dying trees, leaf-less, but still with their bark on. A milky slick shivering on the water.

We heard engines but couldn’t understand where the sound came from.

We screwed Vasiliy’s camera into the quadcopter. And, standing in a clearing, we released it. It quickly became invisible in the low blue of the sky.

Vasiliy laughed.

The sound was coming from a black jeep on the road. Very close – no more than 200 meters away, but the thick underbrush would have made it quite hard to get through to us. We ran, away from the car, away from the road.

We finally caught our breath a kilometer from our destination. We laughed.

A couple of hours later, Vasiliy wrote me, “Come right away.”

We would look at the photos together.

And then, we would see it.

15.

What we’d see is three ramps on the edge of the tailings pond. Little booths on two of them – one yellow, one orange. Hoses threaded through the booths. One end of the hoses rising out of the mirroring surface of the pond, and the other one going over the edge and the road. The road was all dug up, covered in heaps of turned-over dirt. We saw the car that had scared us.

There was a white burst where the hoses touched down on the tundra. And the burst birthed a stream that poured into the dead lake. And out of the lake, into the Kharayelakh. Which flows into Lake Pyasino.

“That’s waste. Fuck, fuck, that’s waste,” Vasiliy said. “They’re dumping RIGHT NOW, after everything!”

He went through the photos. “The resolution is bad, we can’t prove anything.”

He opened the Nornickel Atlas of Raw Minerals, Technological Manufacturing Products and Commercial Production,muttering, “incredible book,” and read aloud, “concentrated waste tailings are comprised of .068% copper, .53% nickel, 37.7% ferrum, .021% cobalt, and 18% sulfur.” He said that when they were exposed to oxygen, these elements changed into their ionic forms and could intermix with water.

Поддержите

нашу работу!

Нажимая кнопку «Стать соучастником»,

я принимаю условия и подтверждаю свое гражданство РФ

Если у вас есть вопросы, пишите [email protected] или звоните:

+7 (929) 612-03-68

He opened Metal Production Beyond the Arctic Circle.Found the chapter on the TEF, and read that, “The following substances are used in flotation processes for concentrates: aerofloat, pine oil, sodium bisulfate, xanthate, sodium diethyldithiocarbamate, active surfactants that are mixed with tailings in tailings storage facilities».

And then, they leave the tailings pond through a hose leading into the tundra. Into the dead lake, the murky stream, the Kharayelakh River, Lake Pyasino, and the Kara Sea.

He said, “We have to go back there.”

16.

Who was we?

We had to get back to the dump site. Three people was really, truly not enough, just one car from the SD could have stopped us.

There was the underground, which Vasiliy didn’t trust. “Someone will blab. As soon as word gets out, they’ll switch off the pumps.”

Vasiliy met with Ruslan Abdullayev next to his building. The fountains off HPP-1 were spraying Dolgoe lake water into the air. Wet young women strolled down the pipes filled with industrial process water. Vasiliy wanted help writing up a report and Ruslan wanted to know, what report? What did you find?

Vasiliy said, “I’ll tell you later. But I need support.”

“You’ll get it.”

He went home. The children were sleeping, exhausted from running through bushes. “They have a whole army down there,” Masha said.

Vasiliy bent his fingers back, silently moving his lips. He wrote the plan out on paper.

“We need time. We need people.”

“Goddamn revolutionaries,” Masha said. “I’m coming with you, brother.”

Irina’s eyes got huge. She nodded, saying nothing.

17.

The Greenpeace activists flew in early in the morning. Iosif Kogotko, Lena Sakirko, and their photographer, Dima. Iosif collects samples. He’s from St. Petersburg, studied forestry, and he’s almost 40 but passes for 20 because of his smile and his curls, shaggy all around his head. Everyone calls him Yos. He’s a raw foodist, doesn’t have a car or smoke. He says that Greenpeace is his family.

Lena Sakriko studied to be a translator, she knows three languages. She got involved with Greenpeace after translating for the activists who were arrested in Murmansk [in 2013 – Trans.]. She’s been a volunteer fireman, putting out wildfires. She’s soft-spoken and does her eye makeup even for going out in the field.

They packed in a rented apartment. Respirator masks, yellow protective coveralls, gloves. Yos instructed us:

“This protective equipment is used by everyone in Greenpeace. Even if it’s superfluous here. We’re dividing the shore up into three zones – a hot zone, where all of the work gets done, a warm decontamination zone for cleaning, and a clean zone where we pack up the samples. I’m going to be the only one in the hot zone, someone needs to help out with the water in the warm zone, and in the cold zone, that’s it, we can take off our coveralls.”

“Now – the sampling equipment. We take off the caps, rinse them 3-5 times, fill the bottle up to the top, and put in the foil stopper. Then we screw the cap back on over the foil. Meanwhile, we’re taking photos and videos. The samples from the bottom are taken from the bow of the boat, the decontaminator dries them off, wipes them down, and packs them up. For soil, we make a square with five points on it, with a meter between them. We dig everything between the five points into one heap and mix it together. That way, we get well-mixed sample out of five individual samples. Remove the rocks and root fragments…”

To choose our testing sites, we looked at satellite images, studying the rivers, the lake, and the wind. We chose eight: where the Ambarnaya River flowed into Lake Pyasino; a creek off the Pyasino River; and eddies and points that had “visible stagnating matter along the stream.” The most distant point was a fishing outpost called Kresty. There were 180 kilometers between the first and last site. We also needed to take a control sample out of the clean tributaries that flow into the Pyasina. The rest of the water and soil would be compared to it.

“The amount we need to get done takes my breath away,” Yos said. “These will be the first samples ever taken from the Pyasina, the very first ones. We’re going to find out.”

19.

But we went. It was like a movie.

We met a man in the aisle of a grocery store and agreed on a time. We “went to bed” for a long time then silently packed our bags and got in the right cars with our phones off. All of our stuff was tossed onto the boat in under a minute.

“Hurry, hurry,” the men pushed the boat off the shore and waved to us with their giant hands.

20.

The lake is right by the city – 15 kilometers, 10 minutes on a hovercraft. When you see those kilometers, you realize there’s completely no way that the diesel didn’t get here during those first 36 hours while they were putting the booms out.

Nadezhda and the Copper Plant waved farewell to us with their smoke. A lens of smog enveloped the city. The captain told us, “We got out just in time. As long as we make it into the river, they won’t touch us. Their luck has run out.”

Blue sleepless eyes. He knew that the other captains were fined, that they were threatened, but he still took us. Why? “I love these places. And I know them every well.”

They say Lake Pyasino is dangerous. The depth ranges from 10 meters to 40 centimeters, the wind meanders over it freely and easily breaks boats apart during storms. But we got through.

The captain said that at the time of the spill, there was ice out beyond Golyj Point. And that the diesel reached Golyj Point.

We entered the Pyasina River behind Chayachy Island. The river was quiet, the water barely sparkling. The tattered forest gradually gave way to true tundra. Hunters’ and fishermen’s shacks dotted the shore. Talovaya, Bludnyj Point, Zaostrovka, Krizhy, Chetvertinka, Chernaya.

We passed a barge from Ust-Avam. The captains waved to each other.

We had breakfast at an abandoned hut. Behind it, reindeer bones lay bleaching in the sun. There used to be thousands-strong herds here. They’ve changed their migration routes: the authorities blame the poachers, but the hunters say it’s the Nornickel pipelines and gas residue on the tundra mosses.

Finally, we reached Kresty.

21.

Kresty stands on a high shore. At one point, there was a weather station here, a hunting, fishing, and gathering management (GosPromKhoz) base, and a store. Abandoned buildings – by all appearances, residential – and crumbling hunks of ice lined the shore. Ice caves in the permafrost and so much rusted metal. The weather tower was overgrown in low grass. Only two of the homes looked inhabitable. Fishermen slowly emerged from them. No Russians here – only Dolgans and Nganasans. Sleepy, distrustful faces. They lit up their cigarettes in unison, looking us up and down. They didn’t invite us in and only answered us monosyllabically.

No, they didn’t see any diesel. There were some oil spots on their nets, but who knows what that was.

No, the water didn’t smell like anything.

And there’s no fish. No fish at all. Not since the spill.

22.

Sergey Elagir is a Dolgan, the strong master of Senkin Point. Zhenya Bogatyrev is a Nganasan, his former classmate. They grew up in Ust-Avam and went to the same school. Now they fish together.

Sergey is a fisherman. He said he would have moved to the city a long time ago if it weren’t for his adoptive father whose dying wish was that he didn’t abandon their homestead.

Their homestead: a house that looks like a ship, the fishing nets, the cooperative. The house was warm. The children were still asleep. His wife Nadezhda put a loaf of bread in the oven and quickly went out.

Sergey poured out some tea and told us, “Don’t worry, the water’s not from the Pyasina. We haven’t drunk that water in a hundred years. Because of the Complex.”

He went on a long monologue about the government, and the relationship between man and state. Then he asked that I didn’t include anything he had said about “politics.” “I can answer for what I say. But there are other people that I am responsible for and I can’t protect them.”

Their cooperative usually manages to bring in 3-4 tons of fish every season. They sell them to the supermarkets in Norilsk.

They catch vendace, round-nosed whitefish, muksun, peled, taimen, grayling, pike, and the endangered Siberian salmon, which can’t be fished. “These used to be wealthy places.”

“For the Taymyr, this is going to be like… Like Chernobyl. For the Pyasina River and therefore for people who live on and around it. And that’s just how it is.”

Sergey and Zhenya went to check the nets they had put out the night before. The river worried, beating against the sides of their boat.

Sergey stopped the engine. Zhenya ran his careful fingers through the net.

The first one was empty.

The second one, empty.

A little pike was tangled up in the third. Sergey picked it up and released it.

“God, it’s never been like this,” Zhenya said.

Sergey turned away and spit in the river. Unthinkable. This river is holy and alive. Except now it’s dead.

23.

There are 7000 Dolgans left, they live all over the Taymyr, but only 700 Nganasans. They live in two villages: Ust-Avam and Volochanka, on the Dudypta River, a tributary of the Pyasina. “The youth don’t remember themselves,” Zhenya said. The elders do, but there are almost none of them left. People in the villages drink, there are murders and suicides, the reindeer ran out back in Soviet times, the GosPromKhoz, which employed hunters, fishermen, and seamstresses, was shut down, middlemen come and buy fish for cut rate prices, oftentimes, paying in vodka. But there are still fishermen grouped into households and cooperatives. They’re young and old men who spend half of the year away from their homes. They fish on the Pyasina River. When you count the cost of fuel and food, a fisherman makes no more than 70 thousand rubles a season. That used to be enough around here. What now?

“We’ll go out on the lakes,” Zhenya said. “We can do that.”

But getting out to the lakes, which are scattered around the tundra, requires more gas. One barrel –two hundred litres – costs 25 thousand rubles here. The fragile balance is ruined.

The Nganasans were probably already doomed, but now their end is clearly in sight.

“They’re abandoned to self-sustenance anyway,” Sergey said. “So now it’ll just be more intense. People will have less to eat. That’s all. So what? What that means… It means they’ll eat plain bread without butter. But maybe there won’t even be any bread… Do you think that half of them, in the situation they’re in already, which has nothing to do with this spill, you think they live well? I mean even in terms of food. It’s not like there’s anything to buy there. People go hungry. They literally go hungry. And they’d be happy to leave, but where can they go? Some of them don’t have any education… Not even basic primary education. That’s how things have worked out. They never thought they’d be stuck in a village and things would turn out like this. That someone would go and spill something into the river and everything would have to change. That communism would end and capitalism would come. That they’d have nothing left to live on.”

The Nganasans had songs called sitabithat they’d sing for whole days straight. They had lullabies, each of which was made up for a child and grew up with her. They had gods, and the mother of underground ice, and the mother of every river.

“In the village, they don’t understand what has happened,” said Zhenya. “Do you?”

How can you assess the cost of the life of an already dying, disappearing people? Who will calculate it and how will anyone dare to?

I don’t know.

24.

There were no fish on Korennaya, or Tsentralnaya, or Kosmofiziki. The fishermen said that they’d killed the river, and after that, they would just swear. Victor from Tsentralnaya said if the fish didn’t come back, he was making a noose, and he laughed, and his laughter was scary.

25.

The captain wanted to go down a creek to hide our boat – you never know what’s coming. But rivers of fog crept over the tundra. We spent the night in a hut called Kurya.

26.

The sound of the helicopter woke us up. It was bright red like nothing else in the tundra, it landed on the shore. Four people stepped out. A uniformed policeman, another one in camouflage, with a mosquito net, and two silent types in civilian clothes, «members of the public.»

Later, the Norilskers would identify them as “FSB Sasha” and head of Nornickel investigative department Vladimir Sazonov.

The “civilians” openly searched the shore. Sazonov got up close and photographed us with a high-quality professional camera.

The policemen said, “We need to search the boat for weapons.” But they wouldn’t touch anything. They needed the captain.

We told them the captain had left to get gas.

The policeman asked Yos what his nationality was.

“I don’t know,” Yos told him.

At a certain point, the policeman decided to enter the hut. He checked under the bunks, under the bench in the sauna, asked to unroll our sleeping bags.

Sazonov examined the toilet.

FSB Sasha droned that it’s no good to lie and they’re going to find the captain one way or another.

“Well, look for him.”

The policemen stepped away to make a call on their satellite phone.

Then they carried the gas belonging to the hut owner out of the hut.

They untied the rest of our gas from the boat. And stole the key out of the ignition.

“You’re going to leave us in the middle of the tundra without any gas?”

“We’ll call in a rescue squad. You can back get to town on what you have.”

“We’re confiscating it! The captain doesn’t have a license to operate, the boat isn’t registered, and you didn’t sign in with the Ministry of Emergency Management!”

They waved around a warrant for yesterday’s captains. Sazonov continued taking photos.

They wrote out a warrant for searching the site. Their formulation: “In order to halt and prevent the group’s advancement we confiscated canisters presumed to hold diesel fuel.”

But the fuel didn’t fit in their helicopter. They had to make two trips to carry it all away.

They spent a long time circling over the woods in search of the captain.

He finally reappeared after the helicopters were gone for good. Angry and jubilant. «Shameless cunts,» he roared.

At the next huts we passed, the people gave us their fuel, which is like gold here. They said, “The helicopter has been looking for you for two days.”

“They killed the lake, they killed the river, and now they’re flying around looking for you, those sons of bitches. Whatever you do, get those samples, get them and take them out of here, and you – write, write about how things are around here, what’s going on right now, write about all of this.”

27.

Yos got the samples. Which wasn’t easy. You have to wash the bottles out really well. Then, the river bottom was rocky and the special scoop that’s activated when it’s struck kept getting snagged on the rocks and coming back open. We made doubles of every sample – we didn’t know which set of them would make it out of here or how. Moscow was trying to figure out the shipping for these little containers of soil and water, but Norilsk isn’t Moscow – we knew that now.

Lena stood several meters away in a yellow coverall with a leaking bag. According to the rules, Yos needed to be decontaminated – washed down with clean water, and only afterwards could they take off their coveralls.

The captain smoked angrily. He was scared now and kept grumbling, “Hurry up, hurry, or else I’m letting you out here. You’ll have to walk back with those tubes of yours.” Watching the low sky for signs of red.

A storm started up on the lake. A mean little wave charged our propeller, making it impossible to get to out to the final site where Vasiliy had photographed the shore covered in diesel. We headed back to the city. Our precious samples packed away, numbered, and secretly marked to avoid being traded out for fakes.

We were quickly unloaded into our cars. The boat, which didn’t have a key, was taken away to be hidden on its last bit of fuel. The captain nodded goodbye. Then he left town.

28.

Nadezhda and the Copper Plant exhaled their regular smoke.

Moscow City Duma Deputy Sergey Mitrokhin arrived sleepy.

He was “led” from the moment he stepped off the plane, a cheerful, blue-eyed young man in blue gloves “recognized him” and offered to help him, asking why he was visiting.

Mitrokhin laughed it off and kept quiet, the young man offered a ride but ended up in his friend’s jeep alone and immediately started making phone calls.

Mitrokhin had come to attempt to take the samples back with him to Moscow.

Before he returned to the airport, the ecologists plied him with tea and planned out what he should do if they tried to confiscate the samples.

“Let’s not even call them samples,” Lena suggested. “It’s just some soil.”

The plan fell apart as soon the first bag went through the x-ray.

“Samples? You got permission from Nornickel?” the air transit safety officer demanded. Then, into her walkie-talkie: “Hurry, second entrance!”

Police appeared with a man in a long trench coat and safety inspector Natalia Vasilievna Abramova.

Everyone openly said that Mitrokhin needed permission from Nornickel. Alexander Gennadievich Stebayev, shift supervisor for air transit safety explained, “The only rules are that you bring on no more than five liters of liquid and that it can’t be combustible. Otherwise, there’s no problem. But you know, we are not free people here, we’re acting on orders.”

“And what is your relationship to Nornickel?”

“Well, we are Nornickel. The airport is Nornickel. It’s a ‘daughter’ company.”