The dispute between bailiffs and opponents of the introduction of QR codes. Photo: Isolda Drobina / Novaya Gazeta

Here what’s in store for you this week:

- This week we investigate the dark side of Russia’s ballooning sex-webcam industry;

- We explain why Russians are pushing back against mandatory Covid-19 QR codes and why it might become the Kremlin’s biggest public challenge in years;

- We expose Russian authorities covering up violations that led to a recent mine disaster;

- Plus, Moscow, we have a garbage problem. The battle against expanding landfills keeps recruiting more Russians.

Want to get the full story? Click the links below for full-length articles in Russian.

Russians vs. QR Codes, Explained

Covid-19 has turned QR codes from something we scan in a grocery store to a major point of political contention — and Russia is on the frontlines of the controversy. This week, our correspondent Irina Drobina spotlights the anti-QR outcry in the country’s fourth-largest city Yekaterinburg. Plus, our columnist Kirill Martynov analyzes why a simple code is so hotly debated, as well as situating the controversy within Russia’s broader political context.

A rally in Kazan (Republic of Tatarstan, Russia) against the introduction of a QR code system. Photo: Artem Dergunov / for Novaya Gazeta

MORE RUSSIAN CITIES PASS QR CODE MANDATES. Moscow was the first Russian city to introduce a QR code system, with people having to show their code — proving vaccination — in order to sit inside cafes, restaurants and bars. While the system lasted in the capital for only a month, several other cities have since taken it on. The federal government had been pondering a nationwide QR code mandate but the backlash faced by the regional authorities who have tried to implement the mandate on a local level is forcing them to think twice about the draft law.

BUT IT DOESN’T SIT WELL WITH THE RUSSIAN PUBLIC. Take Yekaterinburg, the capital of the Sverdlovsk Oblast. On November 29, the regional parliament held a heated discussion of the draft law on the mandatory introduction of electronic certificates in public places and transport. It lasted for three hours. According to Volodymyr Vinnitskiy, Deputy Chairman of the Regional Public Chamber, the chamber received more than 500 questions from the public.

WHY RUSSIANS HATE THEM. The debate came on the heels of a month of protest, including mass pickets, rallies, and even a court case against the governor of Sverdlovsk Oblast, Kuyvashev — demanding the repeal of the QR code system - that included 400 plaintiffs. We can divide the opponents of the proposal into three groups: anti-vaxers, those who fear the transfer of their personal data, and those who believe that the system violates citizens’ constitutional rights. All of them are powered by the country’s traditionally low public trust towards government institutions. One of local anti-QR-code activists Natalya Mukhlynina tells Novaya that by the mandate “we will be deprived of the constitutionally guaranteed rights to freedom of movement, assembly, freedom of entrepreneurial activity, and participation in cultural life.”

AMIDST THE OUTCRY, THERE HAVE BEEN COUNTERPROPOSALS. Human rights activist Sergei Zykov told Novaya: “We need to introduce insurance during vaccination, offer PCR testing […] We need to allow foreign vaccines so that people have a choice.” Meanwhile, Elena Artyukh — the oblast’s business ombudswoman — proposed PCR testing and antibody certificates as alternatives to QR codes.

NEXT STEPS. As a result of the heated public debate, the Public Chamber has drawn up a list of proposed amendments, such as waiving the QR code requirement for people who are travelling for a relative’s funeral and offering an option to delete one’s personal data once the restrictions are no longer in place. On December 7, the Sverdlovsk Regional Duma will consider the appeal of Yekaterinburg residents who oppose compulsory vaccination and the QR code system.

OUR POLITICS EDITOR KIRILL MARTYNOV TAKES A WIDE LENS VIEW OF THE CONTROVERSY, contrasting how Russians responded to the ‘zero-ing’ of Putin’s presidential terms and the persecution of Alexei Navalny, with how they have responded to the possibility of mandatory QR codes. While the first two were met with acquiescence, the latter has elicited an outcry. He argues that the reason for this stark contrast is that the QR code concept touches a very primal nerve, with citizens believing that it “offends their dignity.” Martynov draws a parallel with the aborted 2018 pension reform, which saw tens of thousands of people — many of whom had not previously considered themselves ‘political’ — take to the streets.

PHILOSOPHICAL OBJECTIONS, POLITICAL FEARS. The capitalist and carceral associations are additional reasons for the backlash: “A kind of QR mysticism has appeared”, writes Martynov, “although the code is just a link that is relatively convenient to read in public places, people have associations with barcodes used to label goods (citizens are declaring that «we are not goods»), and also fears that the introduction of QR codes[…] are allegedly connected with the authorities’ ominous plans to build a «digital gulag». Martynov’s final assessment is bleak:

“The QR waltz between society and the state, in which the first partner does not believe in the good intentions of the second and seeks to deceive them at any cost, makes it looks as if we will be stuck with the coronavirus forever.”

BACKSTORY. Russia was the first country in the world to roll out a Covid-19 vaccine. But according to official statistics, only 37 percent of the country's population are fully vaccinated — one of the lowest rates on the continent. Russia's last remaining independent pollster Levada Center recently found that the vast majority of Russians are not willing to be immunized against COVID-19 and the overall vaccination campaign is considered a failure. This is a result of traditionally strong anti-vaxx sentiments in the country and widespread doubts about the quality of Russian-produced vaccines. According to our independent AI-powered COVID-19 tracker, over 640,000 Russians might have died from Covid-19. Official statistics say only 265,000 did. Our investigations have exposed the government «doctoring» both mortality and vaccination rates linked to Covid-19. There is also a high death rate among doctors and a general shortage of personnel in hospitals. Russian doctors are sacrificing everything to save people amid government attempts to silence them from speaking out.

Russia’s Webcam-Sex Industry, Explained

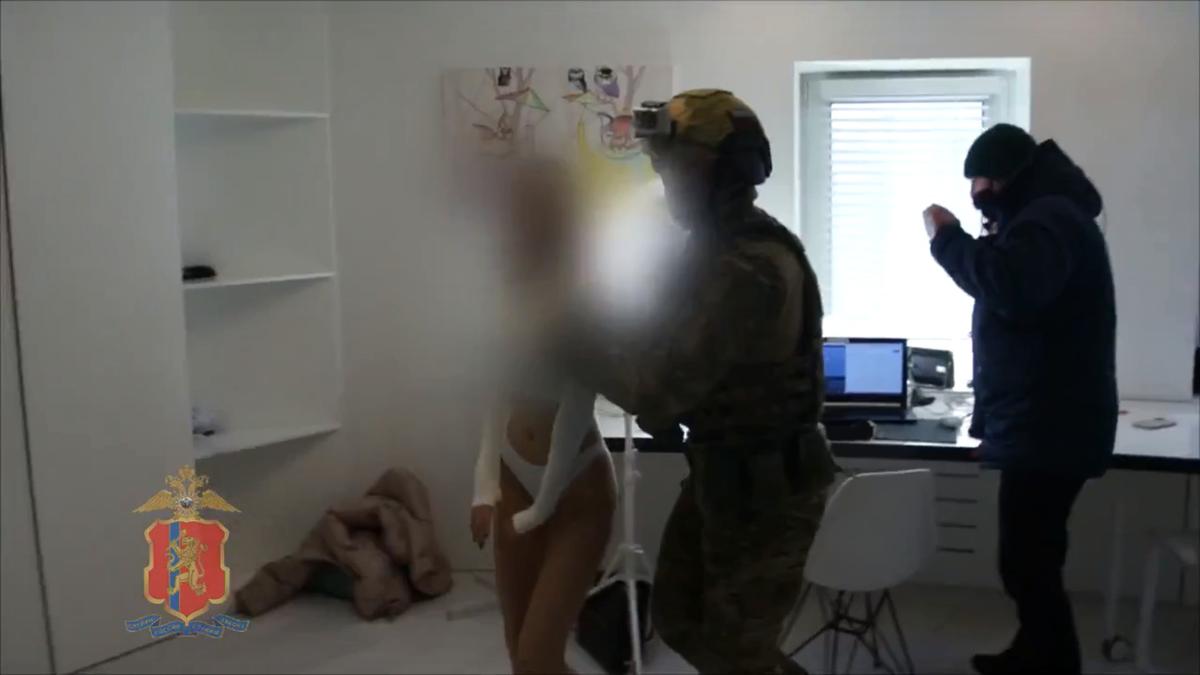

It was a scene straight out of a farce. In mid-July, the Nizhny Novgorod police busted down the door of an office where, a passerby had claimed, there had been sounds of torture. Instead of a chamber of horrors, they found a webcam-sex studio. The groans and screams? All part of the act. Millions of people are stuck at home, and have lost their jobs, because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Unsurprisingly, the webcam-sex industry has boomed. This week, our reporters Tatiana Kuranova, Ivan Zhilin, and Vladimir Prokushev explain how the industry operates, interview some of the men and women who are part of it.

Поддержите

нашу работу!

Нажимая кнопку «Стать соучастником»,

я принимаю условия и подтверждаю свое гражданство РФ

Если у вас есть вопросы, пишите [email protected] или звоните:

+7 (929) 612-03-68

Detention of a webcam model in the studio. Screenshot by police department

OUR INVESTIGATION DISPELS A FEW COMMON MISCONCEPTIONS. Firstly, not all webcam workers are young. Secondly, not all webcam work is for sex. Studio owners told our reporters that the pandemic saw an uptick in people between the ages of 30-40 joining the industry. They also said that webcam interactions are not always about sex, emphasising that many clients simply want to talk. Thirdly, not all webcam workers are women, although they are the majority.

WHY DO THEY JOIN? A perhaps unexpected lure of the industry is social mobility. The webcam business offers a major opportunity to make money without having particularly high education or skills. In vacancies on specialized sites, models are immediately offered income from 100,000 rubles (approximately $1,358). Moreover, one’s income does not depend on Russia’s volatile economic situation since viewers hail from all over the world. Autonomy is another major attraction, says psychotherapist Gennady Averyanov. “Webcams give the employee a feeling of a high level of autonomy: there is no need to «adjust» to a boss, to adapt to a team”, he says. The story of Maria K, a young woman from St. Petersburg, exemplifies both of these attractions. She came to the business because she wanted to move out of her parents’ house.

“I didn't really understand what a webcam was,” she says. — Before that, I worked as a waitress, the salary left much to be desired, and each shift was mentally exhausting. I am from St. Petersburg, and St. Petersburg is called ‘the webcam capital’. One of my acquaintances decided to open his own studio and invited me to work. Maria at first refused, but then decided: «Why not?» In the first shift, she earned 5,000 rubles.

A DOUBLE-EDGED SWORD. Far from being the seedy backroom affair one might imagine, webcam-sex studios can be incredibly luxurious. The MagicMike webcam studio, for example, conducts business in extravagant mansions in the Moscow suburbs, even offering some workers free bed and board. Christina, an employee of the studio, recalls her first day: “Nobody rushed me to get to work. I spent the whole day in the jacuzzi”. There is, of course, a darker side to the industry. Studio owners receive between 30-70% of a worker’s earnings and there is no guarantee of a worker’s safety. Contracts — in the rare cases that they are concluded — have no legal force. Many women told us that their employers exploit them by not not paying the promised bonuses, fining them for being late or substandard work, and even demand sexual favours.

THE WEBCAM-SEX BUSINESS OPERATES IN A LEGAL GREYZONE: it is not directly prohibited, but it can be qualified as the «Illegal production of pornographic materials» (Article 242 of the Criminal Code). The authorities have shown little leniency. In September last year, officers of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the Investigative Committee conducted more than 50 searches in Cherepovets and detained 70 people in connection with the industry. Depending on the exact article under which a defendant is charged, the maximum sentence can range from 6-20 years of imprisonment. But it’s not all doom and gloom for studio owners: no legal status means no taxation, leading to major profits. In Krasnoyarsk, the management of one studio, according to the police, earned 5 million roubles (approximately $67 thousand) a month.

FRIENDS IN HIGH PLACES? Our reporters interviewed Kirill Varichenko who, with extreme reluctance, admitted to being the director of ‘‘MagicMike’ and asked them not to pursue the investigation. Clearly desperate, he added “I am ready to offer you any money. There is too much at stake”. When asked what he meant, he claimed that he had high-ranking relatives and that the investigation would “defame his name”. While webcamming may not be the most conventional business, it — like every other major industry in Russia — is riddled with corruption and shady links to powerful people. Kirill’s claim was truthful. His brother, Philip Varichenko, is the assistant to Chechnya’s tyrannical ruler: Ramzan Kadyrov. To make the situation even more surreal, Philip gained the post in 2016 after winning a reality TV show during which Kadyrov chose the head of the Agency for Strategic Development of the Republic.

Read our full investigation on the ballooning industry here.

St. Petersburg’s Landfill ‘Scourge’, Explained

Russia's environmental record is notoriously poor, with the government’s exploitation of the country’s natural resources in the Far North and Far East regularly making the headlines. A less high-level, but no less dangerous, environmental problem — however — is illegal dumping. This week, Novaya’s Lina Zernova investigates the crisis of unauthorized landfills in Russia’s northern capital.

Landfill near St. Petersburg. Photo by Pavel Lisitsyn / RIA NOVOSTI

THE SCALE OF THE PROBLEM. In 2020, authorities recorded 339 illegal landfills in St. Petersburg, the country’s second largest city. It spends more than one billion roubles (approximately $13.5 million) per year on eliminating them. Municipal deputy Ylia Lebedeva told Zernova: “in the Krasnoselsky district, in three years — from 2018 to 2020 — the regional administration spent about 300 million rubles on the elimination of landfills […] For 300 million, 14 small landfills on the outskirts were cleared. Fighting large ones is much more expensive."

ACCORDING TO THE COMMITTEE FOR NATURE MANAGEMENT OF ST. PETERSBURG, 95% OF UNAUTHORIZED LANDFILLS CONSIST OF CONSTRUCTION WASTE. Unsurprisingly, the criminals hired by construction firms to do their dirty work have little regard for safety, often dumping highly toxic chemical waste near residential areas. Alexander Kuchaev, Deputy Chairman of the Committee for Nature Management, stresses the economic motives: “Wrongdoers want to save money”, he says, so they dump waste illegally to avoid the costs of legitimate waste disposal.

NO ACCOUNTABILITY. While residents can often see the illegal dumping taking place before their very eyes, their appeals are frequently stonewalled. In October, municipal deputy Galina Simonenkova met with the deputy head of the Krasnoselsky administration to raise the problem of an ever-growing construction waste dumps. Simonenkova said that the meeting was suspiciously informal, and that the so-called representatives of the contractor managing the waste disposal did not show any documents proving their identity. “The meeting did not give any results”, she said, “the next day the trucks [carrying waste] arrived again.” In June 2020, residents of the Krasnoselsky and Kirovsky districts submitted written complaints regarding the constant stream of waste — all from a collapsed sports and events complex — being dumped nearby. Nobody responded. The illegal landfill economy, Kuchaev tells Zernova, is “sophisticated” — Both construction firms and criminals know how to cover their financial tracks, so pressing charges is often impossible.

HEALTH RISKS. The criminals managing the illegal dumps frequently set fire to the waste so that they can bring in more and therefore make more profit. The result is not regular fire smoke, but toxic fumes. In March last year, local authorities introduced a state of emergency in Koltushi as fumes from burning paint and varnishes in an illegal dump were causing residents to choke.

BACKSTORY. Illegal dumping and poorly managed landfills are far from being a new problem in Russia. Just last year, a huge fire engulfed an industrial waste site in the Siberian city of Norilsk. Back in 2018, the topic reached the State Duma, with officials estimating that toxic landfills are endangering the health of around 17 million Russians. In 2018, more than one thousand Volokalmsk residents protested to demand the closure of a toxic landfill, which they said was damaging their children’s health. The General Prosecutor’s office reported that its investigations led to the closure of 10,000 illegal landfills between 2016-18. Moreover, environmental degradation remains an ongoing, nationwide issue in Russia, especially as the Kremlin continues to dismantle Russian environmental regulations to maximize the country’s profits from natural resources. These policies provoke more and more man-made ecological disasters and further abuse vulnerable indigenous communities. Growing environmental damage inspiring numerous grassroots eco-movements all across the country — from Shiyes to the Bashkir uprising.

Read Zernova’s full investigation here.

Bonus Round

KUZBASS COVER-UP.

On November 25, tragedy shook the small town of Belovo in Russian Siberia. An excess of methane gas led to an explosion in the local mine — Listvyazhnaya — claiming the lives of 51 people and injuring dozens more. Our special correspondent Elizaveta Kirpanova reports on the aftermath of the Listvyazhnaya mine disaster, and highlights how the local authorities have sought to cover up the negligence that led to the explosion. The biggest revelations?

People at the memorial on the Miners' Walk of Fame. Photo: Svetlana Vidanova / Novaya Gazeta

1) There was a fire in the mine a week before the explosion, but the management did not implement any additional safety measures.

2) The miners knew that the methane levels were too high, but could not report this to management for fear of losing their jobs.

3) It took the authorities 44 minutes to deploy the emergency services to the scene, not 16 as they originally claimed

4) The authorities are pressuring the families of the victims not to speak out about the violations.

The local authorities as well as the mine’s management have promised financial assistance to the survivors and families of the deceased. The latter estimates that each family will receive 6 million roubles ( approximately $81.5 thousand), and each victim 500,000 (approximately $7 thousand). “This”, writes Kirpanova, “is the price of 51 miners' lives and the silence of their families.” Earlier, we already explained the terrible price behind Russian obsession with toxic coal.

This newsletter drop is written and edited by several journalists at the Novaya Gazeta newsroom. Please, support our work by promoting our newsletter with #RussiaExplained hashtag on social media.

To keep up with Novaya Gazeta’s reporting throughout the week, you can follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Telegram. Our video content is available on Youtube and don’t forget to visit our website for the latest stories in Russian.

The Novaya Gazeta Team