This Week’s Highlights

Russia’s parliament presents 12 jaw-dropping draft laws to step up its crackdown on civil society; The Russian Foreign Minister travels to Belarus to publicly back Lukashenka’s dictatorship, and we explain why it was a terrible miscalculation by the Kremlin; plus, the rollout of the Russian Covid-19 vaccine hits roadblocks while the government keeps information about its effectiveness classified.

Want to get the full story? Click the links below for full-length articles in Russian.

Jaw-Dropping Attack on Civil Society, Explained

Over the last decade, the Kremlin has created one of the world's most hostile environments for civil society. The gradual expansion of so-called 'foreign agent' laws made it almost impossible to run organizations that are critical of the government. Now state-controlled lawmakers have put forward 12 draft laws that would effectively curb Russian civil society for good.

WHAT'S IN THE BILLS?The proposed bills are a far-reaching and arbitrary extrapolation of the already existing 'foreign agent' regime. They provide the government with full impunity when cracking down on nonprofits and civil society groups. Authorities could ban nonprofits for almost any activity. They could also implement a total ban on foreign funding, increase fines for participating in demonstrations, detain journalists at rallies, accuse the press of publishing inaccurate information (any critical article can be deemed unreliable), and prohibit 'foreign influence' on educational activities. This last one is also loosely defined. As in the case of extremism, it can be anything the government wants it to be.

EXPANSIVE NEW DEFINITIONS. Under the pretext of fighting foreign interference in Russian politics, lawmakers have suggested that the government amplify the definition of a 'foreign agent.' Now individuals and citizens' associations can also fall into that category if they receive money or any practical assistance from abroad, our columnist Leonid Nikitinsky explains.

"If the bills pass in their current form, Russian society will move to a qualitatively new level of repression," writes expert Sergei Lukashevsky, the head of the country's leading human rights watchdog the 'Sakharov Center.' "A political regime that has embarked on this path of absorbing everything free and independent can no longer stop. The process of grinding down civil society will continue. And if you are against these laws, then you are most likely a 'foreign agent.' Even if you have not received foreign money, that doesn't mean you couldn't potentially seek it out."

WHAT'S NEXT.The Kremlin-controlled majority in the parliament has been working on the draft bills since the summer of 2019. But the process got fast-tracked after Putin solidified his latest power grab earlier this year. The package will get the first reading in mid-December, with final approval expected early next year.

"The bills would allow the term 'foreign agent' to apply to anything that moves, and could criminalize the type of everyday activities that almost all associations are involved in," warns Nikitinsky.

BACKSTORY.The concept of a 'foreign agent' first appeared in Russian legislation in 2012 as amendments to Russia's nonprofit law. They stipulated that nonprofit organizations that receive foreign funding and participate in political activities must identify themselves as 'foreign agents.' But the definition of 'political activity' is very broad, meaning that it extends to a wide variety of organizations, including environmental or animal rights groups, that aren't engaged in explicitly political activity. Meanwhile, domestic funding in Russia is limited, and the Russian state wouldn't give grants to many of these organizations anyway due to their work's critical nature. These organizations are forced to seek support abroad and risk being labeled as a foreign agent, leaving them open to harassment and intimidation.

Read Sergei Lukashevsky’s full analysis of the new bills here, and Leonid Nikitinsky’s breakdown of the bills’ legal history and impact here.

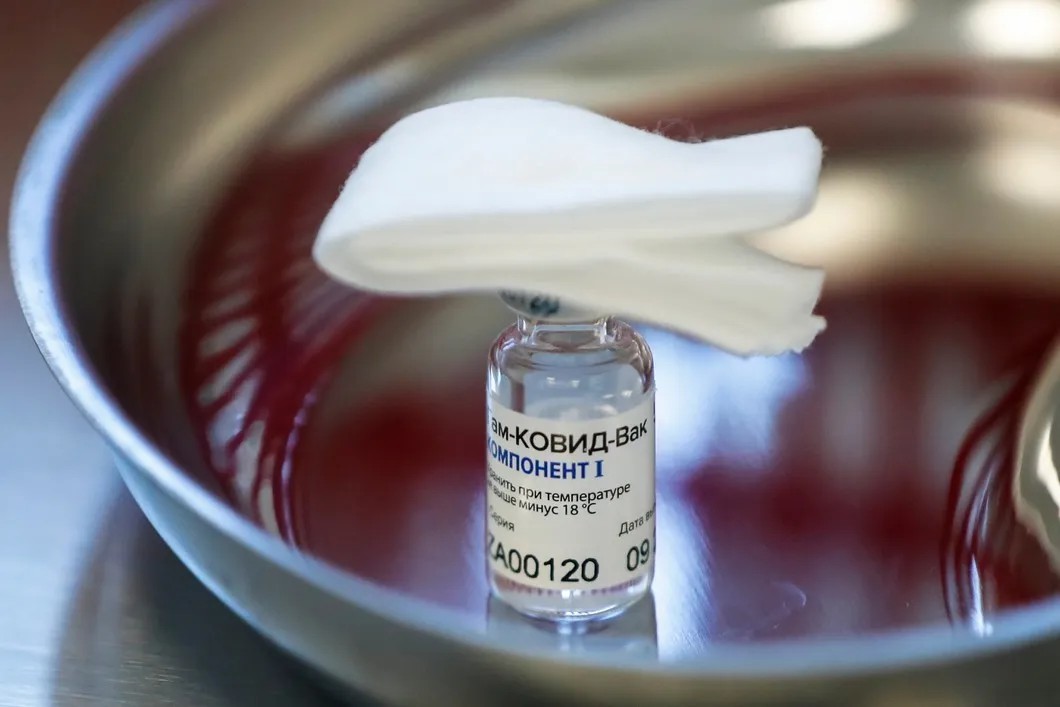

Russia’s Covid-19 Vaccine Hits Roadblocks

Russia has been the epicenter of one of the world’s worst coronavirus outbreaks for months now. While local hospitals were getting overrun, official Covid-19 data was ‘doctored,’ and whistleblowerswere silenced, the Russian elites reportedly gained access to the Sputnik V vaccine as early as this April. Fast-forward eight months later, the Russian government still has zero capacity for mass delivery of domestically-produced vaccines. Even if the Russian-made vaccine is indeed effective (a big if), why should it take so long for regular Russians to get it?

FIRST, BECAUSE THE KREMLIN’S PRIORITIES ARE MISPLACED.Not even a public health catastrophe can distract the Kremlin from its obsession with ‘competing with the West.’ Although the Russian vaccine got fast-track approval back in August, only the U.K. rollout got Putin riled up enough to demand that Russian officials do the same.

SECOND, THE SCALE OF THE VACCINATION EFFORT IS TOO LARGE for Russia’s limited pharma capacities and impoverished, corrupt healthcare system. The state has to deliver the vaccine to around 140 million people and get the vaccination campaign on track. For starters, Russia needs at least 2 million doses produced in the next few days. Deputy Prime Minister Tatyana Golikova says that the state has only 58,000 doses for now, enough to vaccinate just 29,000 people. At the current production speed, it will take years for Russia to vaccinate the population against Covid-19.

Поддержите

нашу работу!

Нажимая кнопку «Стать соучастником»,

я принимаю условия и подтверждаю свое гражданство РФ

Если у вас есть вопросы, пишите [email protected] или звоните:

+7 (929) 612-03-68

SPUTNIK-V MIGHT FALL VICTIM TO RUSSIA’S TECHNOLOGICAL DEGRADATION.It will be impossible to produce large quantities of the vaccine inside Russia, given the country’s aging equipment, warns our columnist Yulia Latynina in this week’s op-ed. The Russian vaccine design is based on the innovative idea of injecting patients with a gene that carries the code for a spike in protein that stimulates an immune response. It is somewhat similar to other successfully approved vaccines by Pfizer and Moderna. But it’s one thing to design a vaccine in a lab, and another to have the means to mass-produce an innovative pharmaceutical product.

“Russia is losing the race to see who can roll out a coronavirus vaccine first,” writes columnist Yulia Latynina. “That’s not because our vaccine is worse. It’s because there is no one and no way to implement its widespread use. Is it possible to assemble a Tesla at a car factory that uses equipment from the 1930s? No. So an advanced vaccine cannot be quickly created on Soviet production lines, either.”

WHAT’S NEXT.Russia might want to outsource the production to places like India. Developed biotechnology production is built on the blockchain principle, and each specialized company performs its part of the work. But in Russia, that model is impossible. Most of the biggest companies are state-run or government-adjacent. The primary source of their income is their administrative utility to the state. Their best marketing bet is to have prescriptions for foreign drugs canceled and replaced with poorly designed substitutes. The companies instructed to produce the Sputnik V vaccine are state-friendly dinosaurs like R-Pharma, Generium, and Binnopharm. They possess impressive administrative resources, but their scientific base is lacking. They are not able to scale up the production of an innovative biotechnology product.

“I have a suspicion that the reason they used so few people in the first and second phases of the Sputnik V clinical trials was not due to malicious intent, but was rather the result of a short supply of the vaccine,” Latynina writes.

BACKSTORY.Russia rushed to produce its domestic vaccine and used it as a toolfor geopolitical competition. It promised to fast-track access for autocratic friends in countries like Hungary and Belarus, for example. Meanwhile, we still know very little about the vaccine. Most of the data on its development and testing remains classified. The government refuses to share it for global peer review. The country has a history of pushing defective drugs as a cure for Covid-19 and silencing whistleblowers who sound the alarm over the way the authorities are responding to the pandemic, a fact that doesn’t exactly inspire confidence. And many of the country’s top scientists and academics have fled abroad due to persecution.

Read Yulia Latynina’s deep dive into Russia’s coronavirus vaccine here.

Kremlin’s Misplaced Bet on Belarusian Dictator

Russia's Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov traveled to Minsk last week, where he pledged that Moscow would fully support Belarussian dictator Alyaksandr Lukashenka. Not only did he appear with the tyrant in front of the cameras, but he condemned alleged "foreign interference in Belarus's internal affairs." This is a terrible bet, warns our deputy editor-in-chief, Andrey Lipsky, in this week's op-ed.

THE WRONG SIDE TO BACK. First, the Kremlin's move is a betrayal of the thousands of Belarussians who have risked beatings, imprisonment, and death to take to the streets and protest in recent months after the Lukashenka regime stole the country's August 9 elections. After over 120 days of non-stop public resistance, the fall of the Belarusian dictatorship is not a question of 'if,' but 'when,' Lipsky warns.

"Every day in Belarus brings the self-proclaimed President Lukashenka closer to condemnation. Not a symbolic condemnation, nor a political one like what has already taken place. Instead, a quite tangible one with bars on the windows and a standard prison uniform in place of a suit. It is clear that this is only a matter of time. That's it. The curtain has fallen, the point of no return has passed," Lipsky continued.

A FAIL FOR RUSSIAN FOREIGN POLICY. According to Lipsky, the visit is also a testament to Russia's chief diplomat's professional and personal failure. During his tenure, Russia not only lost most of the friendly governments along the country's borders, but it has also seen its standing collapse among neighboring societies. His recent appearance in Belarus was another reminder of why that's happened. Lavrov managed to casually insult the Belarussian people by robbing them of agency and suggesting that foreign powers manipulate them. This will spark animosity towards the Kremlin from people who have been otherwise quite friendly to Moscow.

"Lavrov's support for Lukashenka – even if it's not expressed on his behalf or even entirely sincere – can be characterized as support for the sadist head of a neighboring country, and is consequently a dirty move that will cause insurmountable reputational damage," Lipsky writes. "There are long lists of people who have been humiliated, arrested, beaten, mutilated, and murder by Lukashenka's criminal regime. Lavrov will have to answer for that."

BACKSTORY.Russia already has ahistory of interfering in Belarus. As widespread pushback against rigged elections began to grow, Lukashenka rushed to Putin for help. The Kremlin kept a cautious distance but sent a propaganda backup. Lukashenka also has a long history of cooperating with the Kremlin. After taking over Belarus in 1994, he began building an economy closely integrated with Russia and accepted Moscow's geopolitical dominance. But starting around 2014, the Belarusian autocrat began to gravitate away from the Kremlin. That changed following the August elections, however. The European Union condemned Lukashenka's handling of the electoral process. It issued new sanctions for repression and intimidation against peaceful demonstrators and electoral misconduct. With this in mind, Lukashenka's rapid pro-Russian u-turn in the last several months looks like a desperate response to the growing uprising.

Read Andrey Lipsky’s full analysis of Sergei Lavrov’s visit to Belarus here.

Other Top-Stories Russia Has Been Reading

- WHERE DID ALL THE MIGRANTS GO? One of our most-read stories this week is about Russia’s vanishing migrant workers. The coronavirus pandemic has slammed shut borders and consequently transformed Russia’s labor market. According to some estimates, there are around 2.5 million fewer foreign workers in Russia this year. The pervasive xenophobia of Russian society towards foreign workers is no secret, so many cheered the outflow at first. But now, a harsh reality-check is due. Many Russian citizens weren’t willing to take on the type of jobs left by migrant workers, and employers weren’t happy with domestic laborers’ performance. Soon the market began to compete for the few migrants who remained. Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyanin has publicly expressed concern over the issue and its effect on the city that has been the largest employer of foreign (often illegal) labor. Only one out of every ten vacancies has been replaced.

- THE VANISHING ARAL SEA.Another popular story this week is from the epicenter of one of Eurasia’s largest environmental catastrophes. The Aral Sea in Kazakhstan has all but disappeared entirely in recent years. Contrary to its name, the Aral Sea is actually a lake, and once upon a time, it was one of the world’s largest. What was once a thriving and ancient ecosystem is now just a desert tormented by toxic dust storms carrying salt and fertilizer poisons for hundreds of kilometers. A Novaya Gazeta correspondent went to the region to document how locals are desperately trying to make sure the water comes back. “I was five years old when the lake dried up,” says Madi, a local resident. "I would stand on the shores and wait for the waves to wash my feet. The next year, there was only clay in this place. The last time I went swimming was in 1977. Then the port and factories closed, and difficult times came."

- PILLAGING THE ARCTIC OF OIL.Another popular read explains the launch of the Vostok Oil Project - a new oil and gas field that would be one of Russia’s largest industrial projects in history. The state oil monopoly requested from the Kremlin over $100 billion in funding for it. Our economic analyst Maxim Avernbukh questions the economic reasoning behind this costly project set in an extreme environment and amid the global decline of oil consumption. Plus, Vostok Oil can only turn a profit if oil prices stay above $40 a barrel — which is not a safe bet at the moment. With the amount of money that Rosneft is asking for Vostok Oil, one could build 90 highways stretching from Moscow to St. Petersburg and fix every road in the densely populated Western Russia, writes Averbukh. You could also build 4 million new apartments and solve the country’s housing problems for around 8 million people.

Поддержите

нашу работу!

Нажимая кнопку «Стать соучастником»,

я принимаю условия и подтверждаю свое гражданство РФ

Если у вас есть вопросы, пишите [email protected] или звоните:

+7 (929) 612-03-68