This Week’s Highlights

Russia’s security services have arrested dozens of the country’s top scientists for spying; The Ministry of Economic Development presented a new bill that would allow foreigners to obtain a residence permit in exchange for investments; and, Novaya Gazeta investigates a pharmaceutical fraud scheme that made some people rich while killing others.

Want to get the full story? Click the links below for full-length articles in Russian.

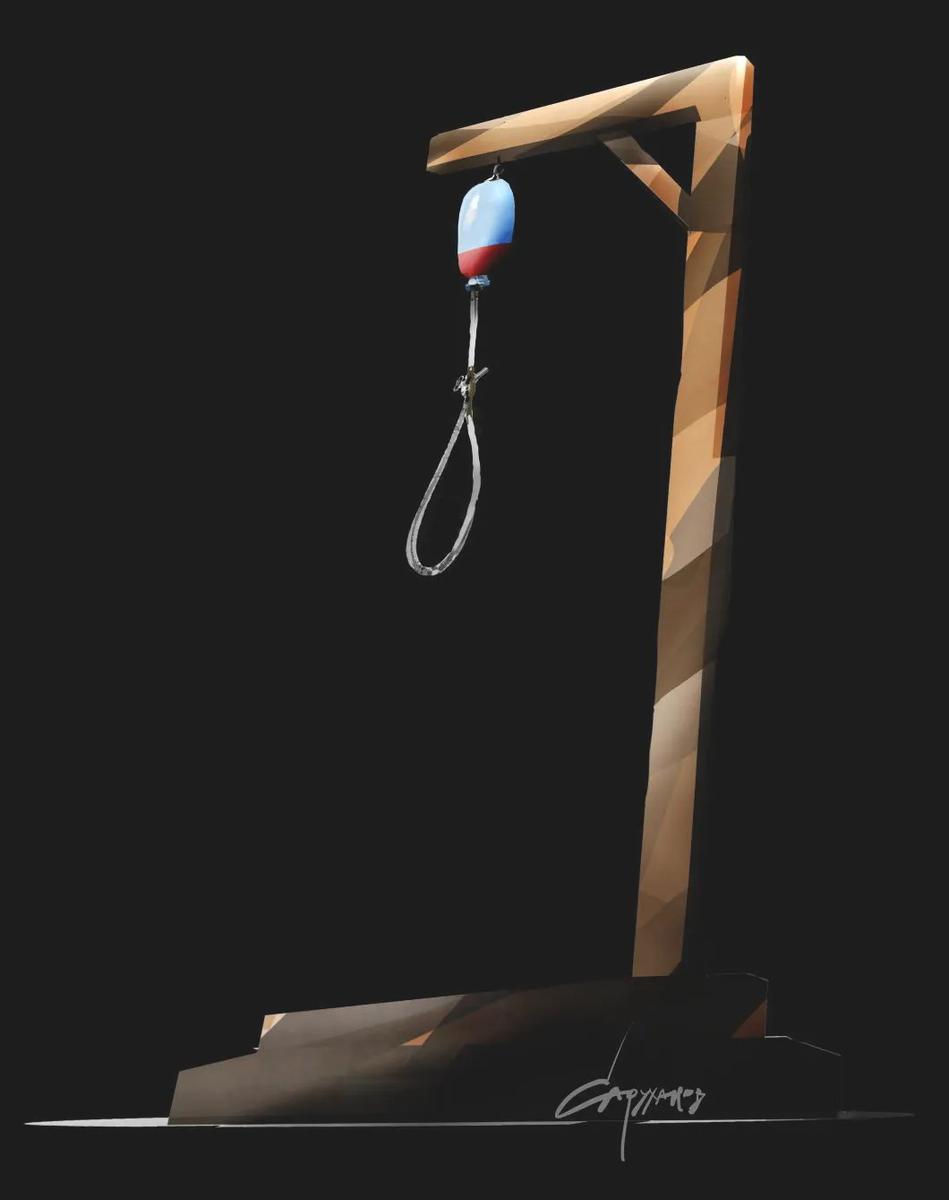

Crackdown on Russian Scientists, Explained

Over the past 20 years, dozens of Russia's top scientists have gone to jail for allegedly spying on the country or committing treason. Hunting "spying scientists" has become a trend in Russia's Federal Security Services (FSB) regional offices, and members of the security services have arrested scientists and academics all across the country. This week our justice correspondent Vera Chelischeva brings us a special investigation crowdfunded by our subscribers.

SCIENTISTS ARE AN EASY TARGET FOR RUSSIA'S FSB.They often travel abroad for work, have access to state secrets, and frequently receive grants from Russia. Most of the cases brought by the FSB are against older scientists with extensive experience. That's because they are more likely to have traveled worldwide and to have a network of contacts in the international community, making them the perfect prey. The FSB, which needs to justify its existence with high-profile arrests, sees treason in every communication that a scientist has abroad.

ARTICLE 275.Another reason for an uptick in this trend is an amendment to Russia's criminal code. While an earlier version of the law defined treason as "assisting a foreign state by carrying out hostile activities to the detriment of Russia's security," the words' hostile' and 'foreign' disappeared from the amended code in 2012. This vague language made it much easier to prosecute people for treason or espionage.

PUBLISH AND PERISH. It's nearly impossible to carry out scientific work without some level of international cooperation and without publishing your work in prestigious foreign academic journals. But currently, the Kremlin seems to want to prevent scientists from publishing their research in foreign academic journals, particularly those belonging to what the state calls 'enemy nations' — most of which happen to be the epicenters of vigorous scientific research. So for Russia's scientists, merely doing your job can land you in jail.

INVESTIGATIONS INTO SCIENTISTS HAVE ZERO TRANSPARENCY.Our investigation looked into numerous cases of recently persecuted Russian scientists. Most of them were carried out behind closed doors. Materials from the cases are classified, and the security services pressure the defendants and their lawyers to sign non-disclosure agreements.

"We simply do not know very much about many of the convicts because both they and their relatives have been intimidated by the FSB and are too afraid to say anything," says Ernst Cherny, a former member of the now-defunct Committee to Protect Scientists. "The investigators are relaxed. They're confident that their cobbled together accusations will slip through all the courts."

FOR TARGETED SCIENTISTS, FEW WAYS TO DEFEND THEMSELVES. Ever since the Committee to Protect Scientists fell apart, there has been almost no independent legal recourse for these scientists. The only legal protection they receive is provided by an association of Russian lawyers and journalists dubbed "Team 29." The group is fighting for Russian citizens' civil rights, and they often defend people accused of high treason. But this group has been unable to keep a whole slew of Russian scientists from being targeted.

THE WORLD MUST KNOW THE NAMES OF UNLAWFULLY PERSECUTED RUSSIAN SCIENTISTS.Here are just two examples of scientists who have suffered for their work in recent years. Our investigation features many more like them, and the outcomes of their cases are all very different.

Academic Victor Akulichev: was charged with smuggling, espionage, and the illegal movement of top-secret weapons abroad. The Committee for the Protection of Scientists defended him. As a result, all of the charges against Akulichev, except the smuggling charges, were dropped. He was sentenced to four years of probation, instead — although the prosecutors failed to prove the charges.

Engineer Anatoly Babkin: At the time of his arrest, Babkin had worked for around 50 years at the Moscow Bauman State Technical University. A talented scientist, he was involved in developing the engineering for the Shkval high-speed submarine torpedo missile. The university had a joint research contract with the University of Pennsylvania and its representative, Edmond Pope, who took over the supply of additional instruments. The Institute appointed Babkin as the Russian representative of this association. When Pope arrived in Moscow for a visit, he was arrested, and the 72-year-old Babkin was also sent to the Lefortovo pre-trial detention center. In February 2003, he was sentenced to eight years in prison and was prohibited from carrying out scientific activities — again based on zero credible evidence.

BACKSTORY.Russian scientists have been persecuted since the time of the Soviet Union when science was exclusively controlled and policed by the state. Scientists were often sent to the Gulags for exhibiting signs of academic freedom. Following the Soviet Union's collapse in 1991, many scientists fled abroad for better jobs and academic freedom. Later, President Putin reestablished the government's control over science, stifling the industry with politics and ideology. This has fuelled brain drain. Even though Russian citizens make up the world's 4th-largest community of scientists, the country tracks in the middle of the Global Innovation Index and has one of the lowest numbers of employed scientists among the countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). A survey by the Boston Consulting Group showed that 50% of Russian scientists would like to work abroad.

Read our deep dive into the FSB’s hunt for Russian scientists here.

Russia’s Weird ‘Golden Passports’ Initiative, Explained

There's a growing public pushback in Europe against so-called 'golden passports and visas,' which give residency rights to the ultra-rich. Many of those are Russians trying to siphon their riches out of their country. Now Russian Ministry of Economic Development has proposed its version of the 'golden passports' program. But it is not designed for foreigners, but for ultra-rich Russians who have swapped their Russian citizenship for foreign 'golden passports' in recent years.

THE PRICE OF BECOMING A RUSSIAN CITIZEN (AGAIN.)The government draft law pending in parliament would allow foreigners to obtain a residence permit in Russia in exchange for 'investments in the Russian economy.' The plan would give foreigners access to a residence permit for a relatively modest sum - roughly between $131K to $395K. One can do it by merely acquiring real estate worth $400K. Ironically, this is the cheapest real estate in Moscow or St. Petersburg. It is also in demand — there are just dozens of such listings available.

LITTLE CHANCE THAT THE OFFER TAKES OFF.According to various estimates, Russians siphoned between $1 and $1,5 trillion out of the country over the last three decades. Russia's Central Bank estimates that the amount of capital leaving Russia has increased two and a half times this year alone and will exceed $50 billion. To make up even for 20% of annual money outflow, the country would need to attract around 50,000 foreign investors — each bringing over $200K into the country. This seems like a tall order given the dearth of investment opportunities in Russia.

"Maybe first make all of Russia's oligarchs and billionaires invest in their own economy? Or pass a law so that various oligarchs and officials do not store tons of cash in foreign luxury apartments instead of investing it in the economy," our economic columnist Dmitry Prokofiev writes in this week's op-ed . "Russian officials could prove the attractiveness of investing in the Russian economy through personal examples," Prokofiev adds with a dash of irony.

Поддержите

нашу работу!

Нажимая кнопку «Стать соучастником»,

я принимаю условия и подтверждаю свое гражданство РФ

Если у вас есть вопросы, пишите [email protected] или звоните:

+7 (929) 612-03-68

DOING BUSINESS IN RUSSIA ISN'T EASY FOR ANY INVESTORS.The Russian government prides itself on doing well in the World Bank's 'Doing Business' ranking. Russia has indeed risen from 120th place to 28th in just eight years. But, paradoxically, these were the same years that economic growth in the country stalled, and citizens' incomes decreased noticeably. Meanwhile, the World Bank has stopped publishing its rating after discovering potential problems with how the data is compiled. Meanwhile, the Heritage Foundation's economic freedom rating, which defines the "degree of non-interference" by the authorities in business processes, has Russia ranked 94th, falling between Honduras and the Dominican Republic. Transparency International also ranked Russia 137th in its corruption index between the Dominican Republic and New Guinea.

BACKSTORY.Like Malta and Cyprus, some European countries have attracted billions of dollars by offering residence permits, and in some cases passports, to foreigners in exchange for investments in those countries. Many Russian oligarchs and corrupt officials have taken advantage of this so-called 'golden passports' program. Thousands of Russians are believed to have invested in Cyprus (and across the EU) to either launder ill-gotten gains or avoid paying taxes. It was only this year that Cyprus opted to scrap the controversial policy.

Read economy columnist Dmitry Prokofiev’s full analysis here.

Russia’s Pharma Fraud, Revealed

This week, we published an investigation by our correspondent Yulia Latynina into a large scale pharmaceutical fraud scheme. She exposes a network of Russian doctors, nurses, public officials, and state healthcare managers who were all stealing life-saving medicines from cancer patients to profit from the black market.

THE BLACK MARKET PHARMA SCHEME.Latynina documents an entire network of doctors and other officials who write fake prescriptions or underfill real ones under the umbrella of a state-funded anti-cancer program. It's not just a matter of having done this a small handful of times. They did it systematically so that they could later sell the drugs they're skimming off the top. The people behind the scheme don't have to pay for the production, licensing, or patents for the drugs. They simply obtain cancer drugs that the state has already paid for and milk money out of them in return. This is how it went down:

THE STORY BEGINS IN 2015,immediately after the Russian biotech company, Biocad created Russia's first drug based on monoclonal antibodies. The drug was known as Acellbia, and the active ingredient is rituximab. Rituximab is one of the most effective chemotherapy drugs for some types of cancer.

A GENERIC CANCER DRUG AT THE EPICENTER. In 2016, the patent for rituximab expired, and biotech companies worldwide began producing generic versions. For Russia's Biocad, this was an ambitious project and the company's calling card. Biocad set out to prove that Russia could create its version of rituximab. That was how Acellbia was born.

FOLLOW PHARMA PROTECTIONISM.Simultaneously, the government issued a decree stating that if there is a generic, Russian-made version of a vital drug, then regional governments can only purchase the Russian version instead of buying a foreign-made version of the same medicine. This greatly benefitted Acellbia, which no longer had to compete against foreign-made versions of the chemotherapy drug.

GOVERNMENT FUNDING HELPED TO FUEL THE SCHEME.The drug Acellbia was later included in the Seven Nosologies program, a government scheme through which the Russian state agreed to pay for specific drugs to treat a designated list of rare diseases. Now Acellbia was not only winning local government tenders; it was getting government subsidies, too.

AND LACK OF OVERSIGHT SUSTAINED IT.This opened an opportunity for unscrupulous actors: pretend that local hospitals and pharmacies need more Acellbia than they do, wait until the government has paid for the drugs, write patients fake prescriptions that inflated the amount of the medicine that they needed, and then sell the excess drugs for personal gain. The scheme fed the black market for pharmaceuticals.

THE HUMAN COSTof this fraud was paid by Russian cancer patients who received drugs sold via the black market. Acellbia needs to be stored in cold temperatures; otherwise, its effectiveness will decrease by 30 to 50 percent. Needless to say, those selling Acellbia on the black market aren't always ensuring that medicines are stored at the right temperature. Patients who take these degraded medicines could die. Even in the best of cases, their chances for survival are reduced.

BACKSTORY. Russia later updated the way it distributes medicines across the country, but that system was less than ideal. The government rolled out a new medicine labeling program this Summer to ensure drug manufacturers can't avoid taxes or sell counterfeit stuff. Each pack of medicine now has a unique ID, a type of digital passport that tracks the journey from the warehouse to the pharmacy. But the idea turned out to be incompatible with the Russian bureaucracy. The new system has left hundreds of thousands of packages of medicines just sitting in warehouses, a Novaya Gazeta investigation discovered.

Read our full investigation into the Russian pharmaceutical industry here.

Other Top-Stories Russia Has Been Reading

- A BRIDGE IN MURMANSK. One of Novaya Gazeta’s most-read stories this week was about a controversial construction project in the northwestern city of Murmansk. The bridge across the Pur River connects a handful of districts with the mainland. It was built over two years, finished ahead of schedule, and was ready for operation 9 months ahead of time. Regional authorities were proud that not a single ruble of state money had been spent. The project was built by private investors, but it soon became clear who was going to pay for the bridge. As soon as it was inaugurated, massive protests broke out because the tolls that trucks had to pay to cross were so exorbitant. Trucks were being charged 370 thousand rubles (roughly $4,860) to cross a bridge that’s less than a mile long. Today very few cars cross the bridge. Even the passenger vehicles that can cross for free are choosing other options.

- THE PEOPLE’S GOVERNOR. Anti-Moscow protests in Siberian city of Khabarovsk have been ongoing for over four months as citizens protest the arrest of the "people's governor" Sergei Furgal. Ilya Azar, special correspondent for Novaya Gazeta, spent a week with the Khabarovsk protesters to understand the reason behind their phenomenal tenacity and ardent love for the arrested head of the region. It was one of our most-read stories. “Before the protests, I just lived a quiet life. I was resigned to the fact that there was such a mess everywhere. Maybe it just didn't concern us before and there was nothing to march for,” one protester told us. “But then in an instant, Sergey Ivanovich united us all. Either you respect yourself and protest until the end, or you don't.”

Thanks for reading!To keep up with Novaya Gazeta’s reporting throughout the week, you can follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Telegram. Our video content is available on Youtube and don’t forget to visit our website for the latest stories in Russian.

— The Novaya Gazeta Team

Поддержите

нашу работу!

Нажимая кнопку «Стать соучастником»,

я принимаю условия и подтверждаю свое гражданство РФ

Если у вас есть вопросы, пишите [email protected] или звоните:

+7 (929) 612-03-68