* In the headline Russian name Vladimir written in German and German name Kurt written in Russian. Means Vladimir and Kurt

Iron Madonna

Only once I heard my father crying. Or better to say: I accidentally overheard it. His friend Misha came to visit him that time, he brought a bottle, they quickly got drunk, and Misha was crying and repeating the same thing:

«I threw stones at them! Do you understand? I threw stones…»

«All the boys threw stones at them,» my father tried to console him.

«But you did not!»

«But I was no longer a boy! I was sixteen! I was already kissing with girls!» my father paused. I could hear Misha sobbing. «I did not throw stones,» my father continued, «I did something worse.»

He stopped talking. Then I heard my dad crying.

«At whom you did not throw stones?» I asked my father the next day after he had already drunken a strong black tea.

«At German prisoners of war. They were building houses on our street. Boys stealthily threw stones at them, women spat in their direction. I gave some bread to one of them — he was very ill. And he silently took this off his neck and handed it to me from below, from the pit that he was digging…» without looking, dad took a matchbox from the bookshelf and let me open it myself. There was a small metal case inside, with an opening lid, and an iron figurine of Mary and the Child lay inside.

«He had been wearing it around his neck throughout the war and he survived. And now, before his death, which was evidently close, he gave it to me, to a stupid boy who brought him a piece of bread… And I've been ashamed all my life because I did not have the right to take it… But I was only sixteen, I did not understand much then.»

He died soon after that, my father, and — strangely enough — it turned out that this penny Madonna from the soldier's neck is the most precious memory I have of my father. It's about something… Something the whole further story is about.

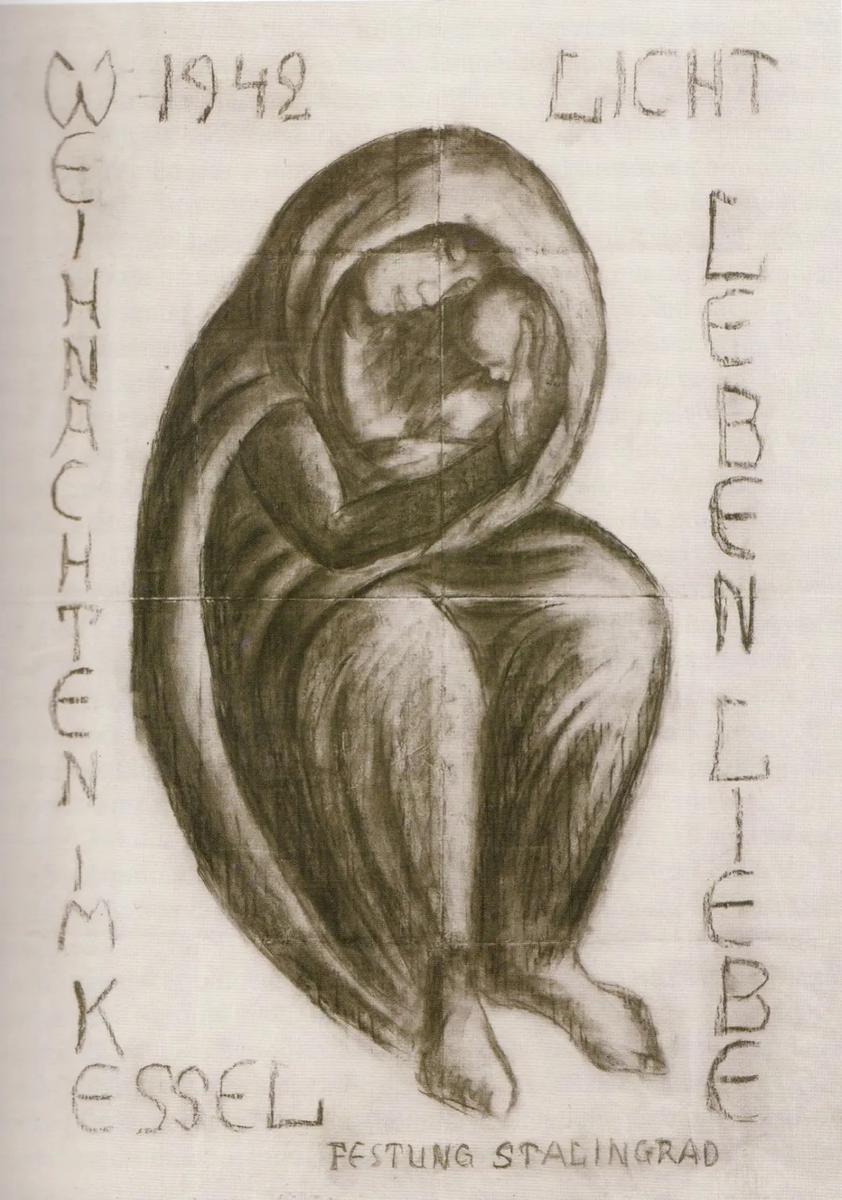

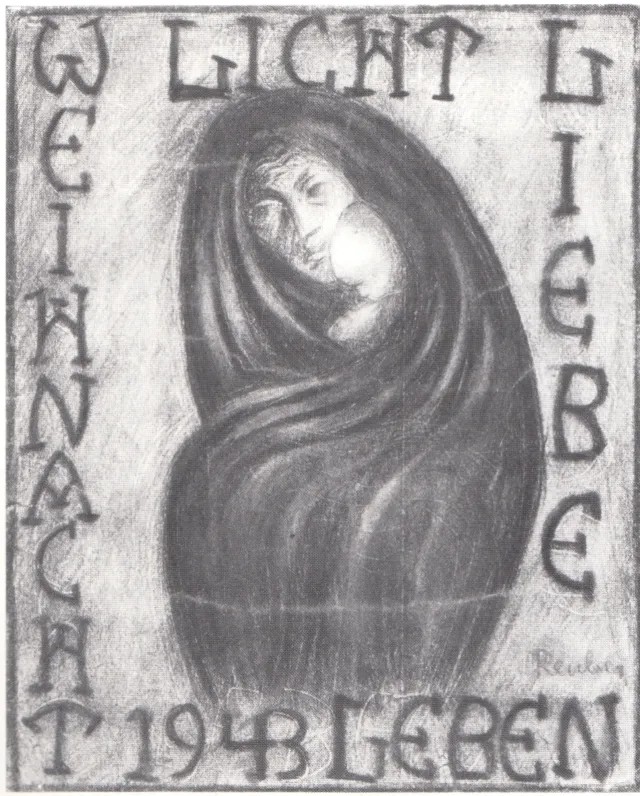

Licht, Leben, Liebe

Maria has bare feet, even though it's cold there. She’s wrapped the baby securely, protecting him from the bad weather, but there’s not enough of the blanket to cover her legs. If it were possible to see the reverse side of this large yellowed piece of paper with noticeable marks from the folds, we would see a geographical map, and familiar names on it: Tschernoje More, Odessa, Cherson, Nikolajew… The war is moving along the map in red lines. And on the other side there is a peace. The child sleeps on Mary's hands. With a quiet smile, she inclined her face to him and closed her eyes. On the right from them there are three words: Licht (Light), Leben (Life), Liebe (Love). On the left: 1942, Christmas under siege, fortress Stalingrad.

«The Stalingrad Madonna»

This is «The Stalingrad Madonna». Under a soft light, it hangs on a black wall in the shadows of the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church in the heart of West Berlin. It was drawn by the German military physician Kurt Reuber.

A friend of Albert Schweitzer, a priest, a talented artist, a humanist, he got his doctor's diploma a year before the war began and volunteered for the front, where he thought he was most needed at that time. Being a part of the 6th Army of the Wehrmacht, Kurt found himself in the trenches of Stalingrad.

«We sit, crouched, in the holes of the steppe ravines. Somehow we dug in and settled down. Dirt and clay. There is nothing but this around us. There is no wood to fortify the dugouts… We have very little water, they bring it from afar. We have enough food to just about not die of hunger… Snow, drizzle, cold, and then suddenly — rain with snow… I haven’t undressed since I got back. Lice. Mice at nights. Sand pours down from above. Everything rumbles around, but we have a good shelter. We share the remnants of the saved food… I remember the beautiful old life with its joys, temptations and love. Everyone dreams of only one thing — to live, to survive! And this is the truth, it might seem rough and primitive. My heart is full: inside of it— serious thoughts about God and the world, outside — the terrible sounds of a destructive slaughter…»

Thousands of people are dying around him every day. Humans kill each other. The doctor, on the contrary, is trying to save. Or at least make it easier to die. He helps everyone he can, without distinguishing between them — be it a German soldier or a Russian old man hiding in the basement of the completely destroyed city. But how much can one person do in the midst of the bloody slaughter, in the frozen hell of Stalingrad? Christmas is coming. For most of them, desperate, exhausted and frostbitten, it will be their last.

«I was not able to talk to anyone, I could only grab my head and silently send the questions of despair into the void, and then God gave me the saving idea to set light, life and love against darkness, death and destruction…»

In a dugout, in the very heart of the most terrible war of mankind, Kurt draws the Madonna with the Child. And for those who look at it, attached to the mud wall, it becomes a consolation. And they sing the Christmas carol «O du fröhliche»: «The world was lost, but Christ is born: rejoice, rejoice, o Christendom!» And they cry. And it makes them feel better for a moment.

Sending his seriously wounded commander on the last plane to leave the Stalingrad siege, Kurt asks him to give his wife Martha a letter and a geographical map with the Madonna. Kurt himself, like the other surviving soldiers and officers of Paulus’s army defeated at Stalingrad, was captured soon after and never returned home.

«When you receive my Christmas letter from the cauldron,» Marta will read, «you will find there a symbol of what we are experiencing now — Christmas in the face of death. A mother who hides in her dark mourning dress a light-faced child… A child is born in the midst of pain and outshines all the darkness and sorrow…»

Light, life, love

Leaning on a cane, 80-year-old Knut Soppa, a former pastor of this church, stands in front of Madonna. During his tenure, in 1983, the children of Kurt Reuber presented to the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church their father’s drawing, which is now consecrated and recognized by various Christian churches as an icon.

«Death ruled in Stalingrad, on both sides, but he wrote «life». He wrote «light» when there was darkness in people's hearts. He wrote «love» when hatred was being preached on both sides so that people were able to kill each other. That’s why I always say: the three words on his icon are the best Christmas sermon…»

The old pastor looks at Her all along. But suddenly he turns to me:

«Why are you interested in Kurt?»

«Humans continue to kill each other. What can we, those for whom war is insanity, do? We can only continue telling stories.»

«How did you even get to know about him?»

And I say to Pastor Knut that it was my 86-year-old friend Vladislav Khlebovich who told me about Kurt Reuber. All his life long he suffered from the fact that he did not remember how his own brother Victor looked like, a brother who was ten years older than him and went missing in the war. Only in 2010 he learned that his brother was killed in a prisoner of war camp exactly at the same time when Kurt drew the Madonna.

My friend Khlebovich believes that Madonna teaches us to resist propaganda. «I remember very well the documentary footage of an endless column of shambling captured German soldiers, they were haggard, hungry and frozen, wearing handmade shoes stuffed with straw and covering their ears with rags. I won’t lie — back then, seening this made me happy and I gloated… And now — I do not have a portrait of my brother, who died in German captivity as a young boy. Instead, there is a portrait of his enemy Kurt Reuber on my desk. I look at him and pray for both. They merge into one…»

Kurt Reuber (on the left) and my grandfather (both pictures were taken before the war)

Rendezvous

Shaking from the gusts of the stormy wind I stood on the old cobbled pavement. If it were not windy, I’d have been completely motionless. I grew up four thousand kilometers from here in a house built by captured Germans. And now I'm standing on the central square of a tiny German city where a Russian soldier, my grandfather, spent three years in captivity.

This is the northwest of Germany, North Frisia, the land of Schleswig-Holstein, Friedrichstadt. I peer into the city. My grandfather’s hands built something here. But what? The houses are all old, the roads too. The wind is icy. The square is empty. All the locals stay home in such weather. There’re not many of them here — two and a half thousand.

But there is an archive and an archivist in this little town which was built in the seventeenth century by the Dutch settlers. I see a bicycle at the entrance. Someone is waiting for me. It is Friday afternoon and the archive should be closed. But they are waiting for me. That is because the city supports this archive precisely for such rare guests as me.

I flip through the dark green sheets with the names of prisoners of war. My grandfather’s isn’t amongst them. The archivist Christiana explains that the SS had managed to destroy almost all the documents before the British army arrived here. Apart from these green archival sheets, there was nothing left of the prisoners in Friedrichstadt.

The wooden stables they lived in have been demolished a long time ago and after that a fire station was built on their spot. In 1961 the remains of the all deceased Soviet prisoners of war were moved from here to the honorary cemetery which is about fifty kilometers away.

«Maybe you personally remember anything about that?» I ask Christiana just in case, she is only a little over fifty. But she does remember! She tells me that her grandfather and grandmother owned a farm outside the city and, like on many others, the prisoners of war worked there.

«When the Russians were released they knocked on their door. And my grandmother was frightened that they would do something bad. But the Russians only asked to give them glasses so they could drink vodka for the victory, and then returned them to my grandmother with the words: «You were feeding us well, so we will not do anything to you». And they left.»

Most likely my grandfather was not able to walk in last months. He was dying. When the British released him he weighed 38 kilograms. I walked through the empty town, along a canal and past small Dutch houses with stepped roofs, and everything inside of me shrank from pain at the thought of this number.

My grandfather seven months after liberation, December 1945, Germany

«Why did you come here?» I asked myself. «Especially since it's so hard. Why?» And I did not have an answer to this question. I did not know it. But I remembered that I always wanted to come to this place. The place where it was so hard for my grandfather.

As if because of the suffering, experienced by him here, this place is now the closest to him. Well, of course! It was my search for a meeting with him. I could talk to him only here. And I wandered along the empty streets. It seemed aimless. It seemed chaotic. Again and again I found myself in front of the fire station. I walked in circles. But as it turned out it made a lot of sense. This is how my rendezvous with my grandfather happened, grandfather whom I had never seen in my life and who in his dying moments was talking about us — unborn grandchildren, that is, about me.

Tears

In terms of dramaturgy the weather the next day was ideal.

The train was going towards Kiel, it was late, I guess it was hard for the train to go against the storm wind. It was blowing at a speed of 53 kilometers per hour. It was blowing and snowing. And you could not see anything around. When I entered the train car there was only one passenger in it, a German of sixty, and we immediately began to talk as if we were acquainted. We laughed as I shook the snow out from underneath my collar. We chattered. We admired the blizzard to the right and to the left of us. He was telling me about the sea shore where he works as a biologist — he watches migratory birds. We admired the white snow again. And then he asked where I was going in such weather. I said: to the cemetery of the captured soldiers.

And he looked at me with such pain that I hastily began to say that my grandfather did not die — he survived, he spent three years here in the camp, he weighed 38 kilograms at the time of liberation, but he survived.

The German was silent for a while, and then began to worry how I would find the cemetery in such weather. I tried to calm him down, I showed him the map, the bus schedule, I said that people would help me. We almost missed my Schleswig.

He led me to the door of the train car, showed me where the train station and the bus stop were (it was not possible to see the station in the snowy mist) and I jumped into the snowdrift. And then I turned around — I wanted to smile at him again as we parted. He was standing by the open door and crying. Tears were rolling down his cheeks one after another. And so we froze for a moment looking at each other: I’m smiling, he’s crying, the wind is blowing, the snow is flying.

Well, and then the train left. I did not even have time to ask his name. It was the third day that I could not cry here, as I were frozen. He did it for me and I felt relieved. I was very grateful to him.

Wladimir and me

The driver of the empty bus loudly announced the name of the cemetery and opened the door. And the next moment I found myself alone in a snowstorm somewhere in the middle of the highway. Strait rows of stalks, perhaps corn, cut off close to the snow-covered ground, stretched off from the road into the whiteness of the fog, and for some reason this picture seemed creepy to me. I could barely see the silhouette of the hill ahead, and I guessed that the honorary cemetery should be there. I was right.

Cemetery of the captured soldiers. Photo: Ekaterina Glikman/«Novaya gazeta»

In good weather there is probably a beautiful view of the huge lake from above. But now I was being blown away. Hiding behind the tree trunk I waited for another snowfall to wane, looking at the long tombstones with the names of soldiers.

Here, all of them lie mixed up: French and Russians, Poles and Estonians, Hungarians and Austrians, Romanians and Dutch… Iwan and Joachim, Heinrich and Aleksei, Karl and Nikolai. If the war lasted several more days, my grandfather Wladimir would have been lying here too and I would not exist at all.

I came down from the hill back to the highway and was standing there in confusion: the bus was not coming soon, there was nowhere to hide from the snowfall, the storm seemed to be only growing stronger. Suddenly a car stopped near me, a door opened and a concerned woman looked out: «Are you all right?»

I nodded: yes, yes.

«But what are you doing here? Alone! In such weather!»

I pointed my finger upwards, towards where the soldiers lay.

«Please, get in the car», the woman insisted.

«But you are going in the opposite direction!»

«We will turn around», she and her husband said in chorus. They drove me to the railway station in Schleswig and asked many times what else they could help me with.

When I returned from Schleswig, I looked at Friedrichstadt with different eyes. I felt at home in it. These tiny Dutch houses one door and one or two windows wide. Ancient doors with forged handles in the form of unseen beasts. Wintering boats on the shore.

The city suddenly came to life, although people continued to hide in their homes. In the footsteps left in the snow it became clear in which of the three city bakeries one can find the most delicious bread and along what paths people prefer to walk the dogs. Between the snowfalls residents came out to clean the sidewalks under their windows, and now you could see who was away.

In the evening, the footsteps led toward the synagogue. You could think that they went there to pray, but there are no more Jews in Friedrichstadt.

The former synagogue is now used as a concert hall. This evening visiting musicians played and sang old songs in Yiddish.

Grandfather’s smile

The snowfall stopped at night. The early morning was frosty. The sun was shining. The train was late. A strange German was standing on the platform: he was smiling. His name was Michael. We chatted all the way to Hamburg. And he confessed at the end what upsets him in his country: «People here are unhappy».

«Isn’t it natural after such history?» I said. «I think Germans and Russians are very close to each other in the amount of pain in our blood».

Michael agreed.

My grandfather smiled all his short life after the camp. He made jokes. He sang songs. He whistled. They said he was an easy man. Therefore, my mother's strongest childhood memory was the moment she caught him in front of the record player: he was listening to the same song and crying. «I'm nervous when I hear French speech…» (It was a very famous song in Soviet Union after the war — translator's note). The French prisoners from the neighboring barrack fed him a little. «I was friends with a Frenchman, I’ll never forget our meetings…»

Before he got to Friedrichstadt my grandfather spent some time in the prison camp of Zandbostel, 43 kilometers from Bremen.

«The Russians arrived in formation, five men in every column. People just bumped into each other and fell, causing their neighbor to fall. None of them could actually walk. The best way to describe them would probably be «walking skeletons». Almost everyone squinted, as the captives did not have the strength to focus their eyesight. They fell on the ground, a whole row at once. The Germans beat them with rifle butts and lashes.

…These poor Russians were in such a state that they could not always adequately perceive reality, understand who and where they are. When we gave them a small part of our food rations it caused terrible fights which the Germans ended by shooting directly into the crowd of people. After these shooting there always remained corpses on the ground.»

A girl with an apple

I stood for a while in front of the Hamburg house of Ute Tolkmitt, Kurt Reuber's daughter, before ringing the bell. I was nervous.

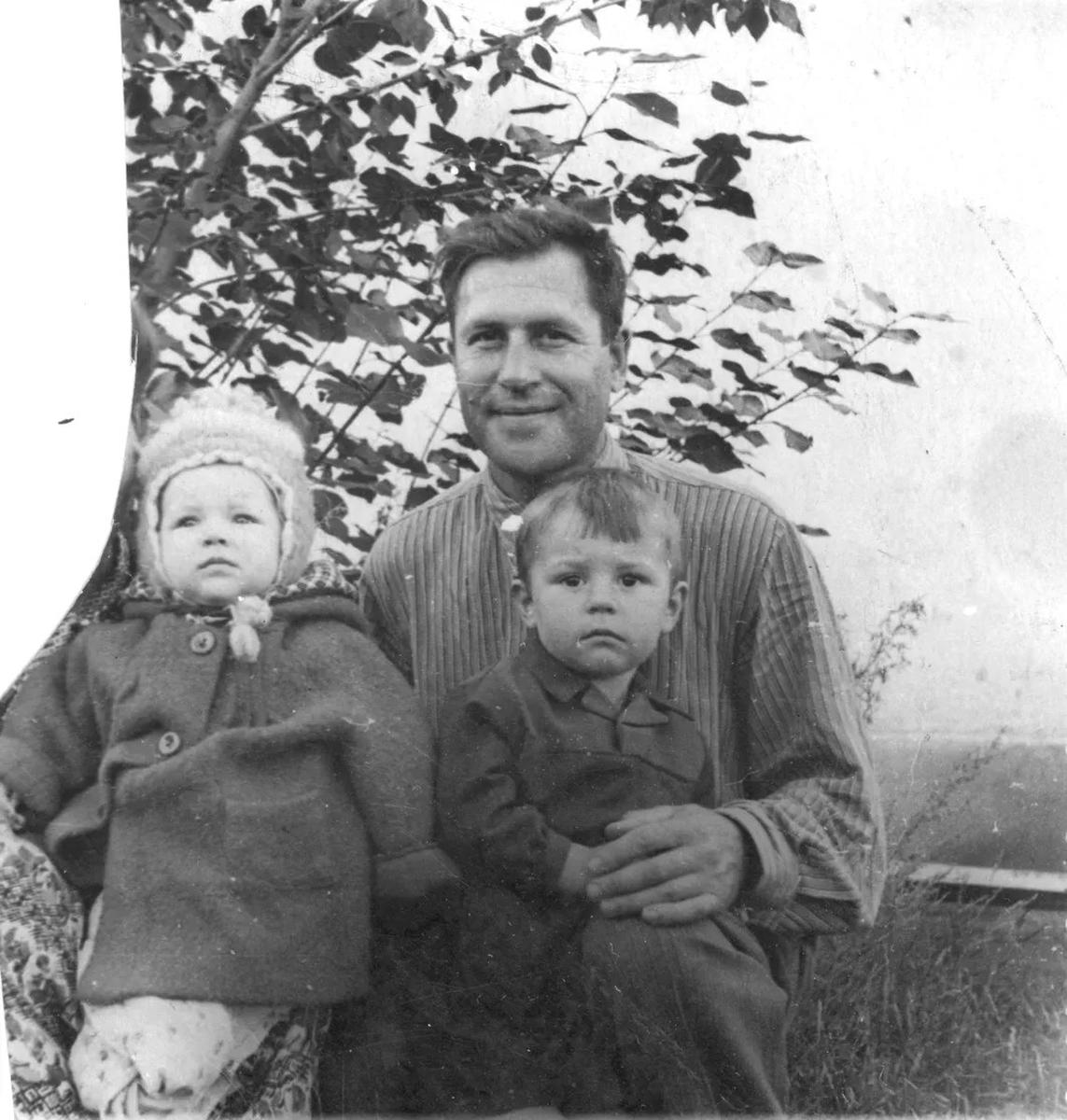

My grandfather helped me. I handed Ute his postwar picture with his children, from which the grandmother's figure was neatly cut off from it (she decided that she had not turned out well).

«And this is my mother,» I pointed to the little girl.

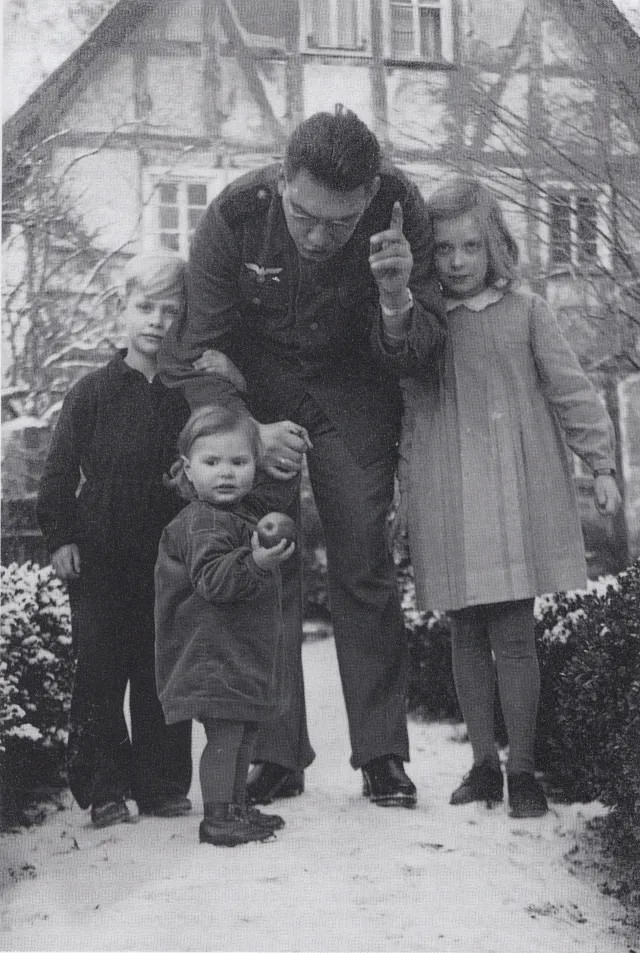

«And this is me,» Ute showed a baby girl of the same age in her photo. She's only three years old on that picture, with an apple in one hand, holding her father’s hand with the other, he is bent over and saying something to her, and her older brother and sister snuggle up to him on both sides.

My grandfather with his kids after the war. My mom is on the left

Kurt Reuber with kids. Autumn 1942. The smallest is Ute

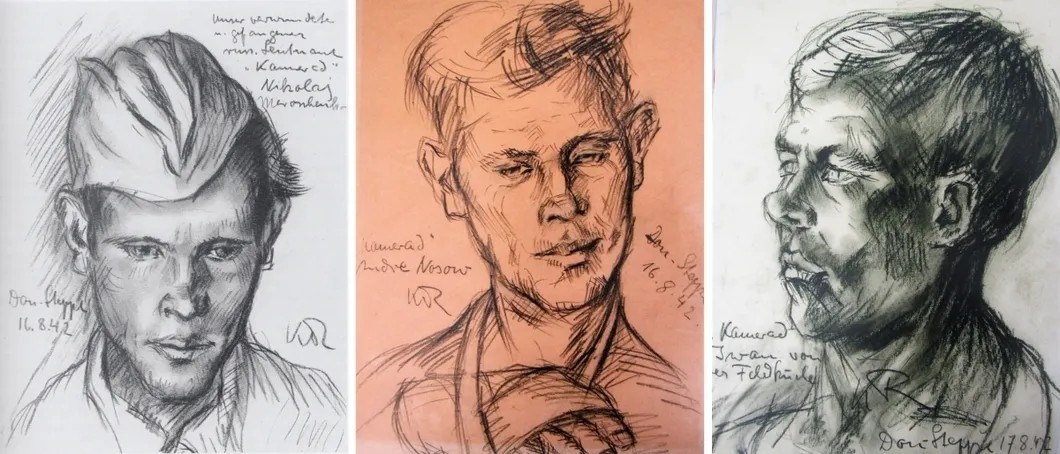

This is the only meeting with her father that she remembers. The elder sister has already passed away. The brother turns 85 this year. Ute is almost 80. It was her, the youngest, who became the keeper of her father’s archive. Me, Ute, her husband Wolf-Dietrich and their son Jan, who looks so similar to his grandfather, are going through Kurt's drawings that he brought back from Russia in October 1942, during his last time off (the photo with the apple was made exactly then). Russian women, old people, children are portrayed on them.

«I constantly peer into the people's faces and cannot tear myself away from them. I can see how the innate Russian melancholy holds in its power over everything — laughter and crying, life affirmation and denial. What kind of dark forces are playing their game here? The Russian person remains a mystery to me in everything. Constantly you face the Slavic soul as an impenetrable wall of fog. And you never know what you'll see when it breaks up: a soft warm light or even more darkness,» Kurt wrote in a letter to his relatives.

«He visited the Russians in their homes, when they were ill, he treated them», explains Wolf-Dietrich, «he did it voluntarily.»

«He talked with them,» Ute adds, «all the portraits are signed: the name of the person who is depicted, the surname, the place, the date.»

«Here are the Russian prisoners of war,» Wolf-Dietrich shows portraits of young guys — one has a side cap on his head, the other is with a bandaged hand. «He signs the drawing: «Kamerad Iwan», «Kamerad Nikolaj». But «kamerad» means even more than a friend.»

The portraits of Russian prisoners of war made by Kurt Reuber

«My father wanted to build a bridge between the Russians and the Germans. He tried to do it during the war!» Ute says.

I recall the words of Kurt Reuber from his last letters: «How many streams of blood and tears have flown through this country,» «We are waging a crusade without a cross. Nazism and Stalinism are both systems created by Satan.»

«You should remember that there was the ideology that time: all Slavs were considered second-class people,» continues Wolf-Dietrich, «these drawings themselves were an act of resistance.»

Some people say that he changed his views and beliefs during the war. Of course this is not true. He spoke out against National Socialism in his sermons. He openly went to a neighboring city to a Jewish tailor for suit fittings. He was under observation. The Gestapo often attended his sermons, even interrogated him, but didn’t really touch him — he was too respected in the village after all. The family thought about emigration to Switzerland. But Reuber said: «I must stay in my village with my parishioners.»

Ute says that he had close connections with a group from Göttingen which was part of the Resistance. Several times before the war he went to Berlin on the affairs of this group. And when a meeting of the leaders of the church took place in his native Kassel, and they actively discussed the cooperation of the church and the state there, one priest strongly opposed this. He was shut up. Reuber stood up for him. For this, some people beat up Reuber after the meeting.

Ute Tolkmitt with her husband Wolf-Dietrich and their son Jan (March 2018). Photo: Ekaterina Glikman/«Novaya gazeta»

All her life Ute wanted to see the very place where her father died. Eventually it happened: in 2005 she and her husband went to Volgograd (former Stalingrad), and from there to Yelabuga where Kurt Reuber is buried. They start to talk almost in chorus. They tell me that in Volgograd a lot of military men in uniform and veterans came to the meeting with them. Ute was sitting on the stage. Suddenly a girl of around fifteen years old came up to her with a bunch of flowers and told her that her grandmother was a child in Stalingrad during the war and had fallen ill, and that Kurt Reuber had cured her. And she survived. The girl thanked Ute and gave her the bouquet.

«Can you imagine the scene?» Jan asked me. I nodded. And then I broke out:

«The world continues to fight and it is unclear what to do about it».

«We need to keep the memory alive!» answered Kurt Rouber's grandson, «for me the example of my grandfather and his life was the reason why I did not go to serve in the army — I went to the hospital. There wasn’t any question. The experience of my family, that pain…»

Home captivity

If to be honest, many of my friends were surprised that I wanted to visit the place where my grandfather has been suffered for three years. «But he did not die there,» they said. To visit the grave — they could just about understand that.

But the director of the Neuengamme’s archive (Neuengamme is the Memorial of the largest concentration camp in the north-west of Germany) Reimer Möller understood me with a half-word: «I would have done the same thing.» «Why?» I asked him. And here is what he told me.

In the late 70's, when he was still a student, he wanted to study the history of German concentration camps during the Second World War. But he was told at the university: this is not history — this is politics, history is what happened in ancient times. He did not agree. There were thirty similar students from Kiel and Hamburg and they began to study this themselves. They met together in pubs, he said, they published their unofficial historical journal.

People told them: go to East Germany! «It felt as if the iron curtain was right here».

«Why did they react this way?» I ask.

«This is a matter of national pride,» Reimer answers. «There were so many losses and unpleasant memories that people wanted to forget all of this. They formulated it in this way: why dig up the past, what’s done is done, we must go forward. I believe there should be no blind zones in history. Otherwise, there will be no progress.»

And the students succeded! Somethings took a long time to happen. But they, when no longer students, did not give up. And it worked. The Neuengamme Memorial was opened for visitors only in 2005. But it was opened! And 5-6 groups of schoolchildren come here every day.

At the end of our conversation Reimer asks me how many years my grandfather spent in the Soviet camp later. I answer that he was lucky: after his release from the German camp he did not immediately return to his homeland — he could not even walk and first of all they put him into the hospital, then he was taken to the headquarters of the Soviet army — there were not enough literate people and a lot of paperwork. So he was lucky. I repeat this phrase again, in Russian now, in a low voice: my grandfather was lucky that after the victory he did not immediately return to his homeland.

And I add: where, after German captivity, he would have been taken to the Soviet prison. Home captivity! Apparently it is necessary to say such phrases in a foreign language more often in order to fully feel what a tragedy it was.

A machine gun and a spoon

The walls of the Museum of Memory of the city of Yelabuga are hung up to the ceiling with portraits of warring countrymen. «Twelve thousand people went to the front through our military enlistment office. Every second was left on the battlefields», says the director of the museum Rosa Ibragimova, she is dressed in military uniform and she has a side cap on her head. Unfortunately, they are still lying there. On the battlefields.

There is only a spoon left from the soldier Semyon Karpovich Novikov. Volunteer searchers found it two years ago in the Tver region, on one of those battlefields. There is nothing else left from Yelabuga townsman Semyon Karpovich. The spoon, lying under a glass display in the museum, is all that remains. For me this was the scariest exhibit there.

Exposition of the museum in Elabuga. Photo: website of the museum

While I'm thinking about the spoon, they suddenly put an army cloak-tent on my shoulders and a helmet on my head. And they give me a machine gun. It turns out that they do this to every visitor. «You must take a picture of yourself before you leave,» they say. It is unbearable to hold a machine gun in your hands after you have seen the spoon.

When you hear «Yelabuga» you almost certainly remember this was the place where Marina Tsvetaeva (famous Russian poet) hanged herself. Perhaps it will come to someone’s mind that this is the birthplace of the painter Ivan Shishkin. Usually there are no other associations with the name. I am no exception: I have not heard anything about this old merchant city on the banks of the Kama River. Therefore, I was terribly surprised to learn that Yelabuga was one of the first Russian cities which was electrified and where a water pipeline was laid (both were built with the money of private donors). Local merchants also built here churches, an orphanage, a charity house, schools (including one for the blind children), a library… — no other county town knew such charity in the pre-revolutionary times. But all that was before the revolution. After that development slowed down. For example, the public laundry, a progressive idea for the middle of the 19th century that was constructed by merchants, was used for its intended purpose until the end of the 20th century.

It was here, in Yelabuga, where the NKVD camp No. 97, perhaps the best known abroad Soviet prison camp, was located. The main contingent here were the officers of the Paulus’ 6th Army who were captured at Stalingrad. This camp can be called exemplary: on its example the whole world had to make sure that Russians were more humane than Germans. The International Committee of the Red Cross sent its teams here.

The camp consisted of Zone A and Zone B. Just as the Germans did, arranging ghettos in the cities of Europe, in Yelabuga too part of the town was closed off for Zone A. But they chose the oldest and the most beautiful part of it — the part where the merchant millionaires lived before the revolution. Merchant houses, old shopping bazaars, stained oak, set parquet, ovens decorated with old tiles, a church, and bullet holes in a wrought fence where many people were shot in 1918, including the merchants themselves.

In what here from 1943 to 1948 that the NKVD, whose headquarters were located in the chicest pre-revolutionary building, tried to turn the captive officers into anti-fascists. Then the camp was liquidated. But the most beautiful part of the city remained closed forever. At first it was a police school. Now a Suvorov military school is located there.

The same pot for everyone

Priest Ilya, parishioner Natalya and senior researcher of the Yelabuga State Museum Ravilia Bruskova are waiting for me in the monastery where the Zone B was located. They are standing outside and basking in the spring sun. The monastery too was built before revolution on the money of Russian merchants. In the 1930s the monastery cathedral was blown up and the nuns were put into Stalin’s prison camps. «After that, street children were placed here, and then the “nemchiki” lived here,» Natalya says. The word «nemchiki» makes me feel uncomfortable. («Nemchiki» — a contemptuous term used to refer to Germans, especially the German soldiers in World War II — translator's note).

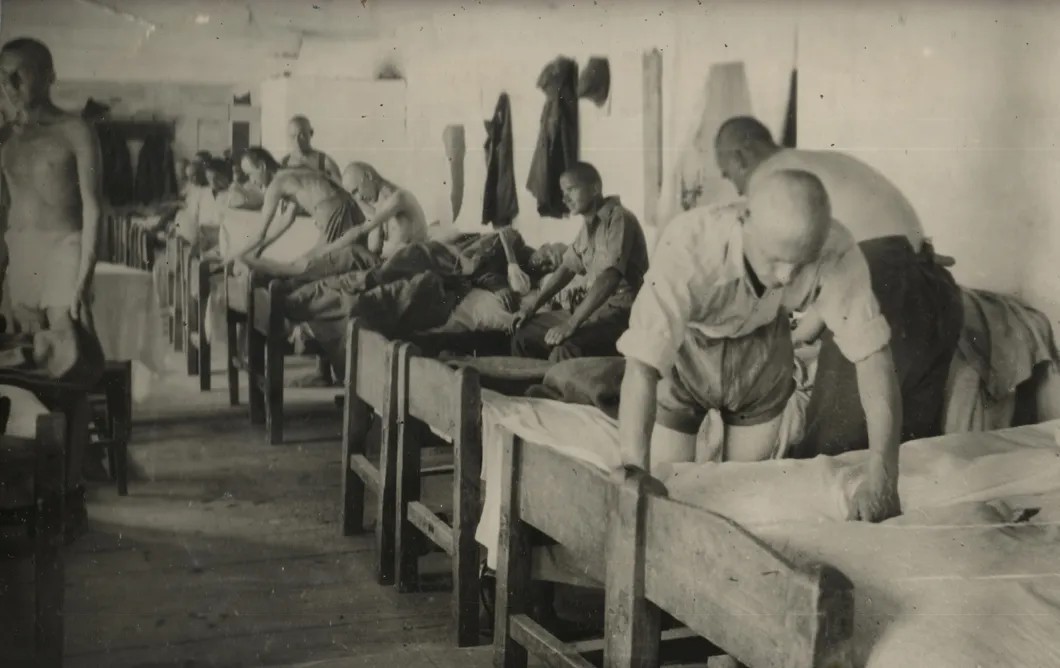

German prisoners of war in Yelabuga. Photo was made by NKVD

Ravilia Bruskova says that at first 5-6 officers died every day — these were the consequences of Stalingrad battle (many Germans were suffering from dystrophy and frostbite). She tells me that the food rations of prisoners of war were better than the rations of nurses who took care of them, even the camp authorities ate food from the same pot as the Germans.

The monastery towers were used as camp towers. Cells of nuns were used as a place to live. Unlike the soldiers, the officers were not used as a free workforce. They only carried out work needed to make the camp self-sufficient. The Germans started a philosophy club, gave lectures on natural science, tried to learn Russian, planted flowers. They had their own theater, orchestra and newspaper…

Here, in this monastery, in January 1944, Kurt Reuber died of the inflammation of the middle ear. He was 37 years old. A month before his death he painted his second Madonna. She was completely different this time. With wrinkles on her forehead, with eyes full of terror. Later she will be called The Prisoners Madonna. He drew it for the newspaper that the captives published and also wrote a «Christmas letter to a German wife and mother.»

The Prisoner’s Madonna. December 1943, Yelabuga

«I know that the shadows of my absence are deep in your eyes — suffering overwhelm you even more when the big and quiet eyes of our children ask you: «Where is dad?» Three times you answered them: «He will return, just wait, next year, soon…» Three times you gave hope to our children. And what about this year? This time too you waited in vain. Christmas has come again — but there is no father.

…Now, in captivity, all I know is that I'm alive. And someone seriously told you that I was missing. How much I am pained by this uncertainty, especially now at Christmas. Surely you searched for me among the hundreds of thousands of victims of Stalingrad, or still among the survivors? Or you already convince yourself that waiting for our meeting is beyond hope?»

This letter Kurt's wife will read after the war, in 1946, when a former prisoner of war will come to her house and bring her this single copy of the newspaper released at Camp No. 97 and the terrible news of the death of the father and husband.

Antifascist club

We enter the old wooden house, we pass through the inner porch and go up to the second floor. «Here they had an anti-fascist club», Natalya says.

«So that's where he drew it!» it dawns on me.

Priest Ilya asks me to show him the reproduction of the Madonna, carefully examines it and says that she does not seem gloomy to him but on the contrary she makes him feel tranquil.

I tell them about Kurt. Natalia asks: «But if he was such a humanist, then why did he go to war?» Priest Ilya agrees: «Yes, it's strange for a priest…»

«For a priest and a humanist it is quite logical — when there is a war, to go to the front as a doctor,» I explain Kurt's actions, «he goes to the place where help is most needed. Even wearing the uniform of the army of invaders this doctor tried to save all the lives that he could — both German and Russian. He was drawing their portraits, he saw in them humans, and not the lowest race. He did everything in defiance of the ideology of his uniform.»

«Today it’s a day of revelation for me!» exclaims Natalia.

And I show them portraits of Russian prisoners — Kurt’s “kamerads”.

«So he is on our side?» Natalia is surprised.

«He is not on our side — he is with everyone. He is a humanist,» I answer her.

«Drawings are made with such a sympathy…» Natalia sighs.

«Was the icon recognized only by Protestants?» priest Ilya asks with an interest.

«No,» I answer, «by everyone.»

«Obviously, it does not look like Russian icons,» says priest Ilya, «but it is like them in spirit. There is depth in it.»

Natalia informs me that they want to make a museum of the monastery here, one room they are going to dedicate to prisoners of war: «We do not want our visitors to have a picture of the prisoners as a gray, faceless mass. We need to tell them about people like Kurt.»

Priest Ilya seems to be bemused by our conversation: «I must find a good copy of the Madonna and hang it here on the wall.»

A relative

The three of us — me, Ravilia Bruskova and the driver — are looking for Kurt Reuber’s name on the memorial plates at the German cemetery. And we cannot find it. We begin to worry. Finally, we realize that the plates are double-sided. Eventually, we find the name. All three feel relieved.

«Was he a relative of yours or what?» the driver is curious.

«We are all relatives. All people are brothers,» Ravilia suddenly says.

«Well, there exist close relatives, and then there are distant ones?» it seems the driver does not understand us.

«This one is close one,» I answer.

And I think to myself that nobody is closer to us, Russians, than the Germans. We have the same nationwide severe trauma. And the residue left behind is only pain. One for all people.

Rejoice!

Children of Kurt did not accidentally choose the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church for the Stalingrad Madonna. Everything here was in ruins after the war. If you stand in the middle of Breitscheidplatz and look around, then out of all the buildings you see there is only one that survived from pre-war time. Well, except the church tower itself. After the war they wanted to take it down. But within a week more than three hundred thousand people wrote letters of protest to the newspapers. They wanted the tower to be preserved. So it stands, with wounds all over its body, with a steeple cut off by the bomb, with empty windows. «The hollow tooth», as the Berliners call it. Inside there is a figure of Christ without his right hand that broke away when the statue fell down. And next to it there’s an unusual cross made out of nails.

Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church

Pastor Knut Soppa told me its story. In November 1940 the British city of Coventry was destroyed during an air raid. And the central cathedral too. The next day after the bombing the abbot of this cathedral came there and saw that the roof had collapsed and the old wooden beams lay on the ground. So they took the iron nails from these beams and made a cross out of them. And they said: this is a sign of the destroyed cathedral and a sign of hope and reconciliation. They installed this cross in the ruins of the altar and wrote only two words under it: «Father, forgive.»

«Do you understand what it means?» the old pastor asks me. «It means: forgive everyone. Not only those who destroyed the cathedral. But us too — who did not do enough to prevent the war. All of us.» And then the British gave the same cross to the Germans and the Russians. And the Germans gave them a copy of the Madonna in return. It was a very solemn ceremony: in the presence of the Queen Mother, the President of Germany and Ute, the daughter of Kurt Reuber, three bishops — British, German and Russian — named the Stalingrad Madonna an icon and consecrated it.

«It was a wonderful time in the late 80's and early 90's,» the pastor sighs, «ВВС broadcasted the service which began in Volgograd, continued in Berlin and ended in Coventry. Nowadays that’s impossible. Then, in the 90's, we all stood with wide-open arms, inviting everyone in a hug. But later we all closed off, began to think only of ourselves, and the situation changed.»

«The world was lost, but Christ is born: rejoice, rejoice, o Christendom!» The world is always lost… I'm standing inside the new Kaiser Wilhelm Church which was built on the foundation of the old one. And Christ with huge pierced palms is floating in the air over me.

It’s semi dark in the church. No noise can be heard from outside. Since morning the sun has been slowly drifting behind the church wall, reflecting in the blue glass cubes it is made from, and shining with blue sunbeams. Now, at noon, it is right behind Christ. And He, surrounded by a blue radiance, unusual, seemingly crucified, with wounds on his palms and feet but without a cross, slightly overhanging us. He is shown at the moment of ascension.

The figure of Christ above the altar in the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church in Berlin. Photo: Ekaterina Glikman/«Novaya gazeta»

«You know, perhaps we will be grateful at the end of our present difficult path that we were forced to go through all the suffering and disappointment, and we will be granted true salvation and liberation, both of the individual and the nation as a whole» Kurt Reuber wrote in the camp for prisoners of war, «But what do most of us understand by the word «peace»? How many are there of those who aspire — in their beliefs, in military disputes — to self-realization as the main goal, while the gloomy war of today is still going. We, prisoners, hear the voice of conscience. Will we follow it? As my deceased kamerad asked me, «will we stop appreciating life?»

Good questions.

Kurt Reuber at war. He is drawing

Translated by Ekaterina Glikman and Ignat Ivlev-Yorke